Pekka Buttler, 15.7.2022

The object of this review is an autofocus lens. Moreover, as Nikon still (as of 2022) sells this lens and makes and sells camera bodies that can natively mount this lens and use it just as well as when it was introduced (in 1989) this lens does not meet the JAPB classification of legacy – instead, it would have to either be rated as current or even new.

On the other hand, the lens design is more than 30 years old and Nikon has since introduced two more modern generations of primes aimed at the same segment (the AF-S 35 mm f/1.8 G ED and the Z 35 mm f/1.8 S), this lens is clearly not an up-to-date lens. Moreover, as it can regularly be had at around 100 € used, this lens is attractive to frugal photographers the world over.

Interestingly, this lens has a mixed reputation. Reviews often hate it, pointing out vignetting and corner softness; while many users – but not all – adore it. Some users eulogise its life-like rendering and colours, its lightness and versatility. Others (both old-timers and legacy lens fans) remember to point out its usability deficiencies (see later). Still others point out that its optical design is comparably unambitious: with only 6 lens elements in 5 groups, this lens’ design is far less sophisticated than either its predecessor (the 8 element 6 group design used by Nikon from 1965–2005 in pre-Ai, Ai, and Ai-s versions) or its successor (the 11 elements in 8 groups design used by the AF-S lens).

It is therefore interesting to see how it performs.

Basics and Specs

The key specifications of the lens have been collected in the table below:

| Lens designation: | AF NIKKOR 35mm 1:2 |

| Manufactured: | 1989–1995 for AF-version; 1995–today (2022) for AF-D version |

| Focal length (zoom range): | 35mm on FullFrame |

| FOV on APS-C/DX Crop | ≈ 52,5 mm on APS-C/ DX Crop |

| Aperture range; clicks | f/2 – f/22; clicks at full stops |

| Aperture blades, type | 7 blades, straight |

| Optical design (elements/groups) | 6 elements in 5 groups |

| Minimum Focus Distance (MFD) | 24 cm |

| Infinity Hard Stop? | Yes |

| Max Magnification: | 1:4,2 |

| Filter Size | 52mm |

| Lens Diameter / length | 65mm / 45mm |

| Lens Weight | 201 grams (measured) |

| Lens hood | • Nikon HN-3 or • any suitable-length 52 mm screw–in hood |

| Mount(s) | Nikon F |

| Related designs (if applicable) | • Nikon has a distinguished genealogy of 35 mm f/2 lenses, that however do not share this lens’ optical design • No similar-design Nikon lens exists |

| Other noteworthy aspects | • The autofocus is of the slot-drive type, which means that it will not autofocus on all Nikon bodies. • There are two variants of this lens, one of the AF-type (introduced 1989) and another of the AF-D subtype (introduced 1995), that are optically identical but the AF-D is able to communicate distance information to a compatible camera body |

| Sample reviewed: | #527114 |

History

The second half of the 1980s saw the introduction of autofocus SLR’s from almost the entire lineup of major Japanese camera manufacturers. While Minolta was first (1985) to introduce such a camera, Nikon, Olympus, Pentax, Canon and Yashica followed quickly (1986–1987).

Importantly, these companies differed significantly in whether their newfangled marvels could use existing optics (albeit, in manual focus). While Minolta, Canon and Yashica introduced new, incompatible lens mounts, Pentax and Nikon opted for facilitating autofocus by extending their existing mount (Olympus’ approach allowed mounting OM glass, but in a crippled form. Read more here). This meant that Minolta and Canon bet the farm, as their AF SLR’s were utterly dependent on the companies managing to quickly launch a broad range of attractive, high-quality lenses, whereas Pentax and Nikon users could fall back on manual lenses, thus allowing the companies to take a more measured approach.

By the end of 1989 Canon had introduced a broad range of 26 lenses (including 11 primes) whereas Nikon (even after a one-year head start) had only introduced 22 new lenses (including 12 primes). Moreover, it would be fair to say that Nikon’s AF lens lineup was somewhat unambitious, as it lacked both long primes as well as the brightest primes. But for Nikon this was sort-of okay, as pros were still sceptical towards autofocus and pros could use their old lenses on the new bodies. Sort-of, because while Nikon pros were not dependent on Nikon’s new AF lenses, there was a threat that a substandard entry into AF would cast a shadow over the legitimacy of the entire company (as happened with Olympus and Yashica).

Problematically for Nikon, many felt that these new AF lenses were tainting the Nikkor brand. They thought the design was too plasticky, the aperture rings were too much geared towards body-based aperture control, and the plastic, ribbed focus rings (for those who wanted to focus manually) were beyond dismal. But most of all, they were (and some still are) appalled by that these new Nikon AF lenses used optical designs that were unsophisticated. Given that three of the new Nikon AF lenses (AF 28/2.8; AF 50/1.8; and AF 70–210/4) were developed from earlier Nikon Series E lenses (Nikon’s Economy series, covered by JAPB here), they were largely correct. Hence, already in 1989, Nikon slightly revised its AF-lens roadmap, introduced improved ergonomics in subsequent designs, and up-spec’ed the ergonomics of many existing lenses, but it would take until ≈ 1993 before Nikon started introducing new, ambitious designs

The lens covered in this review, the AF Nikkor 35 mm f/2, was introduced in 1989 as part of Nikon’s second wave of AF lenses, and – from the onset had a rubber focus ring in the customary location, but its optical scheme (as mentioned above) was significantly more modest than that of Nikon’s previous, similarly spec’ed offering. This alone made sure that owners of Nikon’s existing, and highly regarded manual focus 35/2 lenses were in no hurry to ‘upgrade’.

Even though the lens has its detractors, it is by no means a dog. Unlike the original AF Nikkor 28/2.8 (which was replaced by an optically upgraded design in 1994), this lens design remained optically unchanged throughout its entire production run. And while I cannot say whether Nikon still keeps this lens in production, it can still be had new as of this writing (2022), and that directly from Nikon (not only from retailers’ old stocks). While it is certain that this lens will soon be phased out, the design has remained in production for more than 30 years. That is not a minor accomplishment.

Features

The lens has all the same features as any Nikon AF-D spec prime, including:

– electronic contacts for lens-body communication (will identify the lens to a compatible body and communicate distance information)

– aperture ring (lockable at f/22 to enable camera control of aperture and S/P modes) with full-stop clicks and dual aperture readout

– focus readout window with DOF preview indicators for f/11, 16 and 22 and IR focus dot

– rubberised focus ring (directly coupled) with infinity hard stop

Importantly, the Nikon AF-line of lenses has high compatibility with a wide range of Nikon SLR bodies:

• Nikon AF/AF-D can auto-focus on all Nikon bodies that have an internal focusing motor and are able to drive the slot-drive screw.

• On low-end Nikon dSLR’s that lack the internal autofocus motor, the lenses work at least as well as Nikon’s Ai/Ai-s lenses

• Nikon AF/AF-D lenses are always Ai-s spec, which means they are full compatible with all Nikon Pre-AF cameras that communicate aperture information using Ai or Ai-s principles.

• Nikon AF/AF-D lenses aperture rings have pilot holes to ease the aftermarket mounting of rabbit ears, thus making AF/AF-D lenses useable even on Pre-Ai bodies (as far back as the 1959 Nikon F).

• distance readout window

• aperture lock switch

• pilot holes in aperture ring.

Back-to-front

• 5 Electronic contacts (spring-loaded) for lens–camera communication

• Nikon F-mount

• Aperture ring

• Aperture lock switch

• Focus distance readout window

• Rubberized focus ring

• 52 mm filter threads for mounting filters or hood.

Handling

As is customary, we’ll discuss handling both with an eye to those camera bodies which utilise the full feature set, as well as for bodies which do not use all the features.

Common handling characteristics:

Overall, the AF Nikkor 35 mm f/2 is a relatively small lens (for being a reasonably bright, semi-wide angle) and – at only a tad over 200 grams – a very light lens. That lightness is a tell-tale of a construction wherein the entire outer shell of the lens is made of black, somewhat glossy plastic. Its control ring arrangement (aperture ring at the mount-end; focus ring towards the front of the lens) is customary.

While the lens has an overall very clean, cylindrical shape its inner barrel (that houses the objective) moves out significantly when focusing towards MFD. Simultaneously, that significant extension is reflective of the lens’ rather short MFD.

Left: at infinity.

Right: at MFD.

Handling in the lens’ intended milieu:

When mounted on a Nikon body that supports slot-drive autofocus (and in program/full auto), the lens is almost point-and-shoot as any manipulation of the lens becomes superfluous. However, when the lens is being used either in aperture priority or full auto, manipulation of the aperture ring becomes necessary.

At that stage, the relative failings of the aperture ring become apparent. Firstly, the lens has only full-stop clicks. Secondly, and compared to most legacy lenses (both Nikkors and others), the aperture ring feels both a bit rough and stiff to use.

When used on a Nikon camera that does not facilitate autofocus (either a pre-AF body, or a dSLR that lacks the internal AF motor), the lens can still be focused manually. Here it becomes obvious that the lens’ focus ring almost entirely lacks resistance. Whether this is to the photographer’s liking varies, but it does make unintentional (mis)adjustment of focus rather more likely.

Handling when used as adapted:

The Nikon F mount has a rather generous flange focal distance. Even so, the Canon EF mount is the only full-frame dSLR mount that allows mounting Nikon F lenses on an adapter without corrective optics without losing infinity focus. With all modern mirrorless systems (digital medium format included), the point of flange focal distance becomes a non-issue.

Importantly, Nikon F lenses’ aperture is directly controlled by the aperture ring (without needing any contraptions in the adapter), meaning that all Nikon F lenses work like a charm on any mirrorless system. Also, the functionality offered by this lens’ electronic contacts are in no way critical to the use of such a lens (remember, this lens was supposed to work also on pre-AF Nikon bodies), which means that smart adapters are not necessary. In fact, you can use this lens on the same adapter as you can use any Nikkor pre-Ai, Ai, or Ai-s lens.

While it is easy to eulogise about using legacy Nikkor lenses when adapted to mirrorless, with AF/AF-D lenses such as this lens, there are some potential drawbacks. If one of your attractions to using legacy lenses on mirrorless is the tactile experience of using a legacy lens, then this lens will disappoint you: Firstly, the lens’ barrel is entirely plastic. Secondly, the focus ring offers almost no resistance. Finally, the aperture ring is decidedly rough.

Optics:

The AF Nikkor 35 mm f/2 is a reasonably fast semi-wide lens, and promises to be suitable for many kinds of photography, ranging from travel/landscape to some close-range photography. Using a rather modest 6 elements in 5 groups design, the lens promises a combination of largish maximum aperture, small size and versatility. Let’s see what it delivers.

Definition and contrast (a.k.a. ‘sharpness’)

• JAPB differentiates between the two components of ‘sharpness’: definition and contrast. Read more here on why we do so.

• JAPB always tests definition and contrast both at short and at long range, because some lenses are optimised for short range work and others are optimised for distant targets.

Short-range work

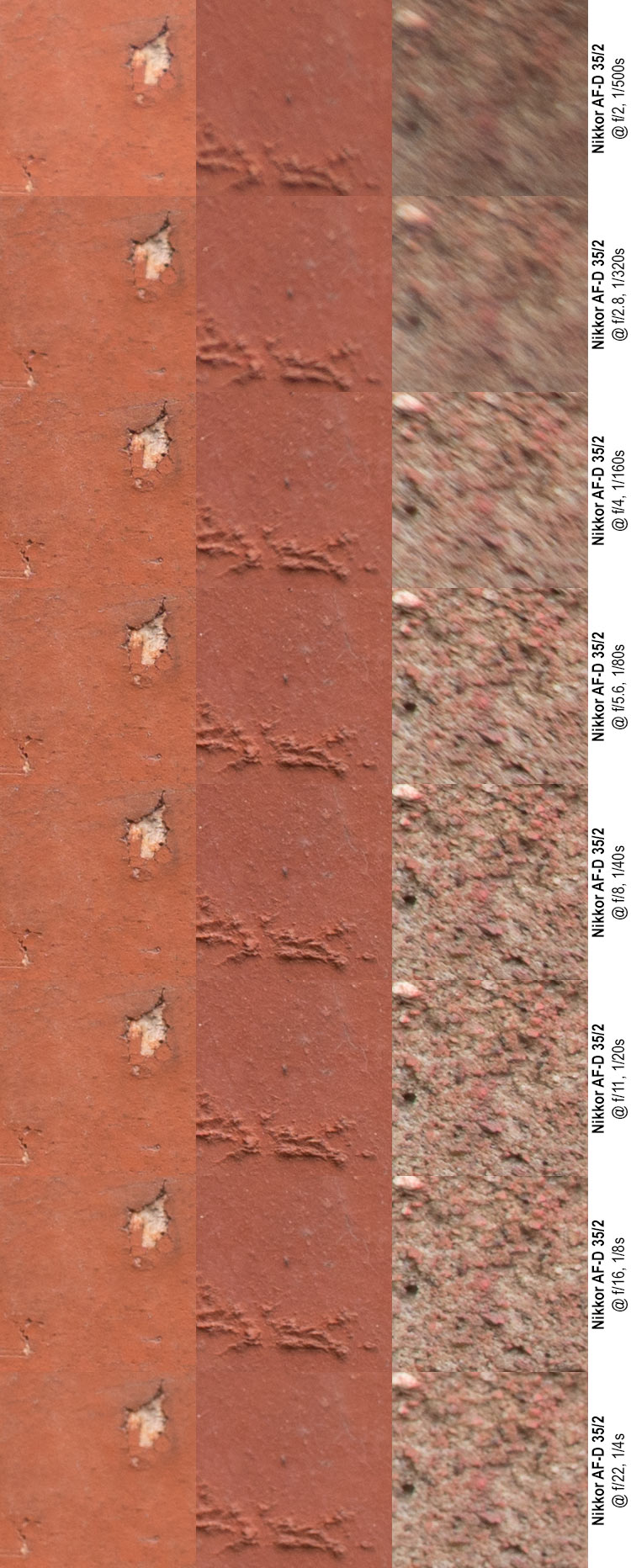

For assessing short-range definition and contrast, the brick wall test is useful, even though it depends on negligent field curvature and therefore does not really give a realistic image of the lens’ abilities.

Mid: Off-centre sample

Right: Corner sample

Quick analysis:

• In the centre the AF Nikkor shows some wide-open spherical aberration and ensuing lack of contrast, but even wide open the image has good definition and decent contrast. Contrast picks up by f/2.8 and definition reaches good levels by f/4. While peak sharpness is at f/8, there no field-relevant difference in the entire f/4–f/11 range.

• Off-centre the AF Nikkor has decent contrast from wide open, but definition is a tad weak wide open. Definition picks up when stopping down, and by f/5.6 the result is good, even though it improves further when going to f/8 and f/11.

• Wide open and at f/2.8 the AF Nikkor shows field-relevant vignetting in the corner.

• Corner crops have weak contrast and bad definition at f/2–f/2.8 and also show signs of detail smearing (likely a symptom of astigmatism and field curvature). While sharpness is not in the cards in the wide open– f/4 range and f/5.6 is still a bit sub-par, by f/8 the AF Nikkor reaches good levels.

• At wide open and f/2.8 it also shows significant vignetting. While the vignetting is gone by f/4, the corners reach their best level at f/5.6.

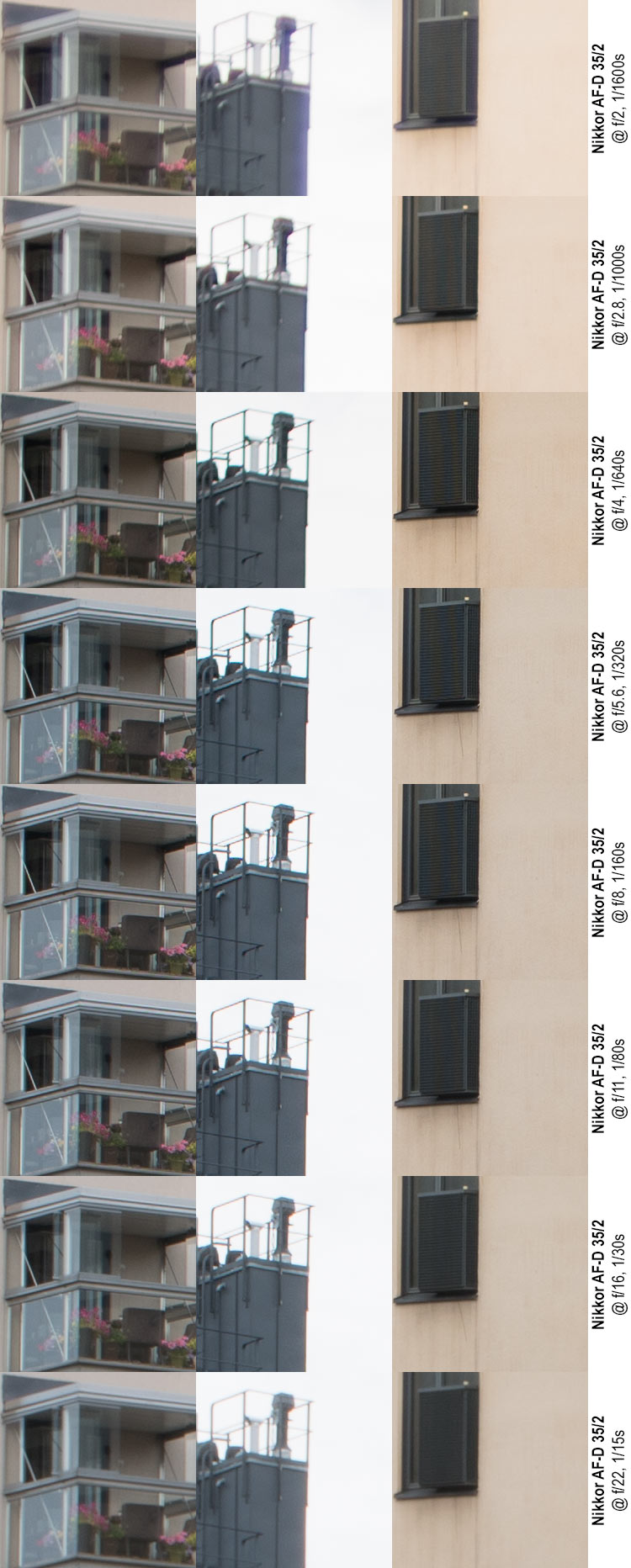

Distant targets

Mid: Off-centre sample

Right: Border sample

Note: Different colour tones are caused by mild changes in lighting conditions

Quick analysis:

• In the centre the AF Nikkor shows some wide-open spherical aberration and ensuing lack of contrast, but contrast picks up by f/2.8 and definition reaches good levels by f/4. Peak sharpness is at f/5.6–f/11.

• Off-centre the AF Nikkor is a mixed bag. Firstly the samples shows significant chromatic aberrations (both longitudinal and lateral) wide open, and while there certainly is a “sweet spot” (when those reach a local minimal), they never entirely go away (admittedly, the sample is quite brutal). Also, and this is especially visible at medium apertures, it is interesting to see that those CA’s seem to affect structures differently depending on whether they are sagittal or tangential (in this sample: horizontal or vertical).

• On the other hand, looking away from the CA’s the AF Nikkor produces decent off-centre sharpness at f/2–f/2.8, good at f/4 and great from f/5.6 to f/11.

• At the border (note: not corner) the AF Nikkor shows some unsharpness wide open and at f/2.8, but improves significantly at f/4 and reaches decent levels at f/5.6.

Quick summation re: definition and contrast

Assuming you’re not expecting corners to be sharp before f/4–f/5.6, the AF Nikkor is a decent little lens. While it does struggle with chromatic aberrations in extreme transitions, it otherwise is able to render imagery with a high level of detail and contrast at medium apertures.

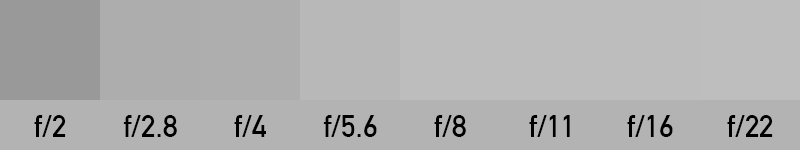

Vignetting

The AF Nikkor does vignette somewhat (what lens does not?), but its vignetting characteristic is by no means extreme. The samples below are 100×100 pixel excerpts of absolute corners (from a Sony ⍺7R2’s 7952×5304 files), which show that while vignetting is otherwise decent once stopped down to f/2.8, the absolute corners keep getting lighter until f/8.

Distortions

The AF Nikkor shows minor barrel distortion (about average for a lens in this class), but the distortion is not of a mixed/mustache type and can easily be corrected in any half-decent photo editor (Photoshop’s lens correction tool will fix the distortion with a value of approximately +2,50).

While these types of distortions are easily fixed with digital images, the AF Nikkor’s mild distortion means that the when using in distortion-critical work (e.g. architecture) on film, the photographer should pay attention.

Out-of-focus character

Disclaimer: The quality of out-of-focus areas (a.k.a. ‘Bokeh’) is not only highly subjective, but also very much dependent on the relative distances (to subject and to background). Hence these samples should be seen not as definitive but as exemplars.

(right-click and open image in new tab for bigger version)

(right-click and open image in new tab for bigger version)

(right-click and open image in new tab for bigger version)

(right-click and open image in new tab for bigger version)

Quick analysis:

Overall the AF Nikkor’s background out-of-focus characteristics are quite nice, and the transition zones seem rather well behaved. Also, while I quite often find wide-open background blur to be distracting and generally tend to prefer backgrounds when stopped down a notch the AF Nikkor wide open is not half-bad (not better or worse than at f/2.8, just different).

Out-of-focus highlight (‘bokeh balls’) show some optical vignetting wide open, but are otherwise well corrected. At f/2.8 the shape of the aperture starts becoming visible and by f/4 a pronounced heptagon isvisible.

Color reproduction

As the AF Nikkor shows neither a tendency towards cool or warm colors, I would have to describe it as ‘balanced’

Flare and veiling

Nikon has always been among those optical companies known for the quality of their coatings. Moreover, this lens is relatively modern. As a result, its ability to handle backlight is comparatively good (see samples), but if flare and veiling are anathema for you, using a lens hood is nevertheless recommended.

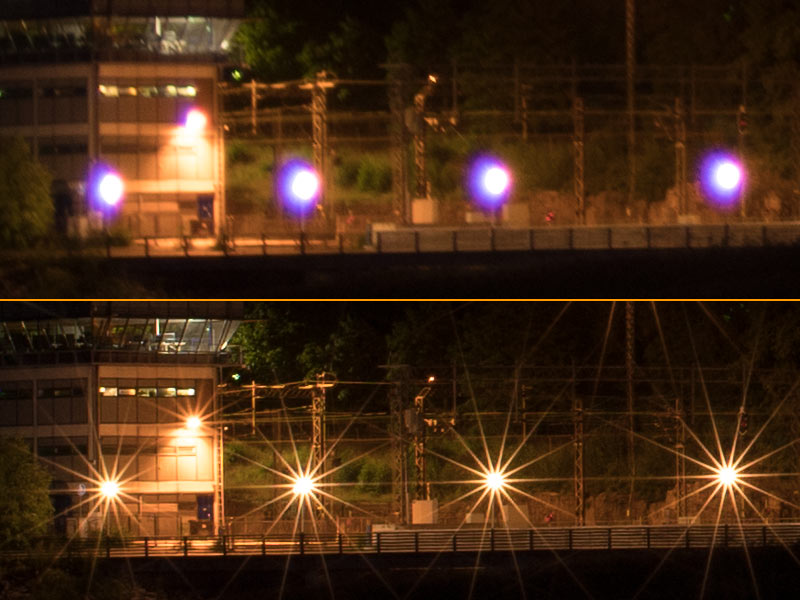

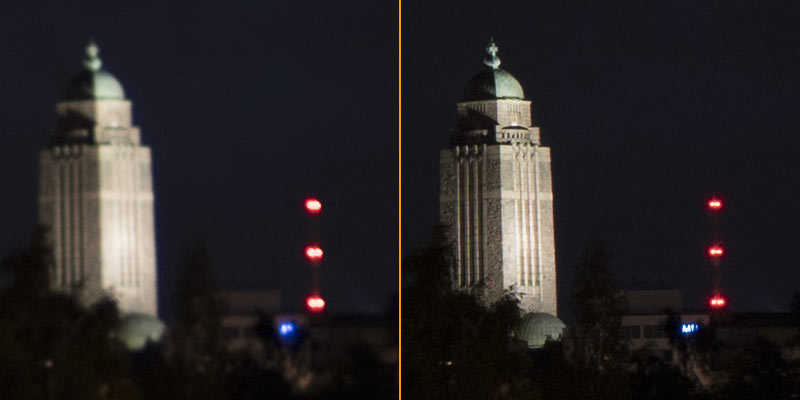

However, when used wide open in night vistas, point light-sources have a tendency to produce some veiling flare (the excerpts below are from the absolute image centre)

Top: wide open (f/2)

Bottom: @ f/5.6

With its uneven number of straight aperture blades, the AF Nikkor has the ability to produce some quite fantastic sunstars.

CA’s, Coma, haloing, etc.

Note please: many sites say a lens suffers coma, when in fact the issue is astigmatism. Read up on the subject in the JAPB articles on comatic aberration (coma) and astigmatism.

Left: wide open (f/2)

Right: @ f/5.6

Left: Original image resized to 1365×2048

Right: excerpts (1:1) from original full-size image

(right click image and open in new tab for larger version)

While the AF Nikkor has some tendency towards veiling flare, it would seem to not suffer only minor astigmatism (visible only in extreme circumstances) and no discernible comatic aberration. (However, I managed to bungle the focusing of the shot a bit)

Summary:

The AF-D Nikkor 35 mm f/2 is a small, light, and versatile lens that – although it has its weaknesses (it’s neither a modern, nor a real legacy lens; tactility when adapted; limitations in IQ) – manages to produce more than decent imagery. I recommend readers to see the lens in perspective (with other similar lenses), by having a look at the JAPB comparison of nine fast 35 mm lenses.

Sample shots:

All shots unprocessed (ACR default, no edit, no crop) only resized.