Pekka Buttler, June 2020

Few lens defects arouse as much emotion and are as surrounded by false or dubious facts as lens Fungus. This makes fungus an obvious choice for the second part in our series of typical defects you may find on legacy lenses.

Again, we will look at lens fungus briefly, but try to cover fungus from all the angles. We’ll start with a short discussion of what lens fungus is, then look at how lens fungus comes to be, before discussing the seriousness of lens fungus and what can be done about it.

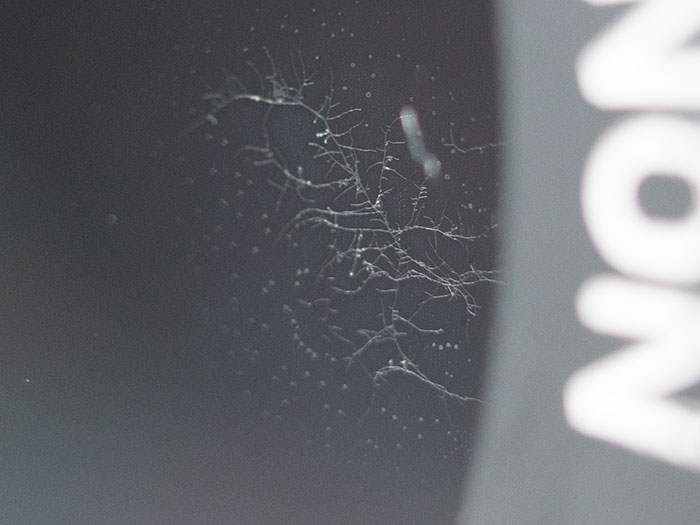

Photographed with Sony ⍺7R2, Nikkor 35mm f/1.4 @ f/4 with 26 mm extension rings

How to identify fungus?

First off, whether you’re browsing photo forums or youtube videos, there are a lot of people who either cannot or do not want to distinguish between fungus (this article), haze (the next article), or element separation. The distinction is nevertheless worthwhile, because the diagnosis has significant effects on the prognosis.

How to tell fungus from haze or separation? When you get down to it, it’s relatively simple: a fungus is a living organism and it grows in a specific way. A fungus always has a dendritic structure (if you will, you can liken the structure of a fungus to that of a root network), it has tendrils and strands, and even when an entire element surface is covered by fungus, it still looks fibrous.

What is lens fungus?

Lens fungus is pretty much a normal fungus – not of the edible variety, but of that variety which largely forms the basis of the entire ecosystem’s decomposition-related activities. The only thing which makes lens fungus different, is that this fungus happens to reside inside a lens (fungus on the outside of a lens is just the same stuff, but that we tend to ignore).

Humanity has traditionally had a problematic relationship with fungus, because whenever we encounter it (such as on mouldy bread), it tends to annoy, even disgust us, but most humans never see, nor understand the absolutely crucial role fungi play in the very ecosystem we rely on, as well as having many other functions humans have become attached to. In fact, fungi are crucial for baking as well as brewing.

Given this problematic relationship, the annoyance and disgust we feel when encountering by lens fungus, is – sadly – in keeping. What is problematic (IMNSHO), is that the disgust we may feel towards fungus and the ignorance with which we treat it has lead to absolutely counterfactual and outright crazy ideas circulating in discussions concerning lenses. This article, in its own, minor way, tries to bring some sense back into the discussion.

Side note: if you do not know much about fungi in general, I recommend to read the Wikipedia article on fungus, as it may help you get a grip on the basics.

Then again, if you’re an adherent of the TL;DR -religion (in which case JAPB might not be for you): Fungus is not a plant, lens fungus will not grow into mushrooms which sprout out of cracks in your lens’ housing, and lens fungus is not the start of an alien invasion.

How can a lens get fungus, and why did mine get it?

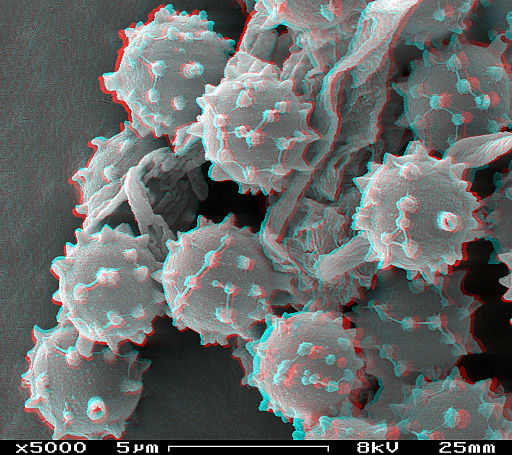

Fungus spreads through spores (you can, if you will, liken them to seeds). Some of these spores are too small to see with the naked eye, while others can be visible with a magnifying glass or macro lens. Fungal spores are airborne, and they reach absolutely everywhere. Actually, if you ever encounter a mycologist and think how boring their professional life must be, ask them to describe some of the more inventive ways fungi use to make sure their spores spread wide.

Clean rooms manage to keep fungal spores out – most of the time – but in the places where photographers roam, you can be certain of an abundance of spores. If you’d bother to investigate your lens innards, with a scanning electron microscope, you’re sure to find fungal spores, and they’d look pretty much like the picture below.

But – and I’m going to continue with that analogy to seeds – just as buying a bag of carrot seeds, and then forgetting that bag into a kitchen drawer does not lead to a carrot explosion, the mere existence of fungal spores in a lens does not lead to a visible lens fungus growing. Just as with those seeds, other circumstances also need to be available to benefit growth. For a fungal spore to start growing, it needs a suitable temperature, water and nutrients. Furthermore draft and UV-radiation inhibit fungal growth.

Problematically, lenses are an almost ideal place for fungus to thrive. Almost.

Water droplets are mostly readily available through condensation. You keep your lenses indoors (e.g. 20c, 60% relative humidity), and after a short while that air permeates your lens innards. You take the lens out to photograph a cold, starlit night (e.g. -10c), and bang! Condensation droplets start forming inside the lens. Then you take your lens back indoors, and the the temperature rises to figures the spores can appreciate. Likewise, with the lens being an enclosed space, which spends most of the time indoors, covered by lens caps at both ends, draft and UV radiation can do little to inhibit fungal growth.

Luckily, it’s not that bad. Firstly, even a periodic dose of UV can stop fungal growth (of most fungi), and those condensation droplets mentioned earlier typically evaporate relatively quickly (in most climates). But most importantly, lenses (and especially lens surfaces) are typically not a prime source of the nutrients a fungus needs.I said ‘typically’, because even the residue one careless fingerprint leaves on a lens element’s surface is more than enough for a veritable bloom.

An interesting aspect with lens fungus is, that it can look really, really bad, even though the biomass of a fungus which looks like it covers an entire lens element cannot even me measured in micrograms (you need smaller units). Fungus on a lens looks dramatic, because it is in the light-path and the growth is almost entirely two-dimensional. When you look at a lens element covered with fungus, think of Flatland.

Incidentally, if you’re in the practice of repairing lenses, watch out, as a single breadcrumb or dandruff flake can be the start of a new wave of fungus.

Anyway, back to business: If your lens has suddenly developed fungus, one of three reasons are the culprit in a majority of cases: (your) climate, that you do not use the lens often enough, and that the fungus has something to feed on.

How serious is lens fungus?

Photographed with Sony ⍺7R2, Nikkor 35mm f/1.4 @ f/4 with 26 mm extension rings

Photographed with Sony ⍺7R2, micro Nikkor 100 mm f4 (pre-Ai) @ f/8

Notice that the fungal growth has taken snowflake-like form. Nature tends to repeat its successes.

With this lens the fungus resides so far into the lens, that it shows only faintly except when backlit.

Well, it can certainly look very dramatic, and it certainly has a significant detrimental effect on resale value, but there might be no discernible effect on image quality.

And this is where we reach into the realm of internet horror stories, so lets begin with debunking some counterfactual statements about lens fungus.

Firstly, lens fungus is not contagious. You do not need to throw away the affected lens, or package it in a sealed plastic bag to protect your other lenses (they all have spores already). Lens fungus does also not lead to sensor fungus – a phenomenon often hinted at, but for which I’ve yet to find a really trustworthy first-hand account – because, let’s face it, if fungal spores can reach inside a lens between the elements, they will sure as hell land on your sensor every time you switch lenses.

Secondly, lens fungus does not lead to a clear drop in IQ. There are, and we’l get back to this, some situations in which lens fungus may impact image quality, but even then that effect is typically real-life -minimal.

Thirdly, lens fungus does not necessarily destroy coatings. Yes, there are reported, trustworthy cases in which that has happened, but with my to-date experience (roughly 50 lenses successfully cleaned of fungus), I’ve yet to encounter a lens where – after removing the fungus – any harm has been done to either coatings or glass. I think that we can call ourself lucky that with more than 100 000 species of fungus, only a minority of fungi secrete a chemical which has the ability to degrade coatings.

Fourthly, removing fungus from lens surfaces is not difficult. The hard parts of the process are getting access to the affected lens elements while trying to make sure not to make matters worse in the long run by depositing organic material (fungie-food) inside the lens. If you want a reason to borrow your spouse’s or model’s hydrogen peroxide or like sniffing ammonia, find another one. Lens fungus typically does not necessitate either (see tips).

But there are some real issues:

Firstly, as noted, there are cases where lens fungi have eroded coatings, and as much as some would like to have you believe otherwise, that hardly is the end of the world. It’s only the coating, not the actual lens, and whatever added reflections a partially scarred coating may produce, are most typically on the order of minuscule. While the resale value will take a tumble, it will hardly affect your lens’ ability to take stunning pictures.

Secondly, and especially when the fungus is towards the rear of the lens-element-stack, fungus may have a discernible effect on image quality. The primary reason for why you won’t able to see fungus in the final image is that fungus tends to primarily form around the edges of lens elements (which generally contribute very little to the image on the sensor anyhow). Secondly, while whatever minor irregularities in the evenness of the air-glass -interface may be caused by the fungus, those can have a discernible effect on the resulting image only when the fungus is on the rearward lens elements (we’ll get back to why this is, when discussing dust and debris)

Thirdly, it’s ugly – even disgusting, and may distract your model.

What can be done about lens fungus?

Simply put, fungus can be removed, and most often with no lasting effect. That said, unless you’re in the rare situation in which fungus has a discernible effect on image quality, there is no need rush. What you should make sure to do is to stop the fungus spreading by means of UV-light (exposure to sun or UV-lamp). Estimates on how long a treatment is needed vary, but my guess is that we’re talking about minutes rather than hours. After you’ve done that, you can have the fungus treated next time you routinely take your lens to the mechanic for a CLA.

Alternatively, you may choose to treat the problem yourself.

WARNING: This is not a lens repair blog, so I will not give you details on the task. Also, unless you have some experience of lens repair and an inkling of what the task entails, either take the lens to a professional, sell it to someone more repair-adept (remember to disclose the lens’ failings), or relegate it to your display cabinet.

There are, however, two tips I will disclose about fungus removal:

Firstly, make sure not to make matters worse. Work on a clean surface, with a clean pair of gloves (and try not to touch your face with those gloves, because they will not be clean after that), and avoid bending over the lens to lessen the risk of something (sweat, dandruff, breadcrumbs) falling off your head and into the lens. Surgical garb is overkill, but tucking your hair under a beanie helps a lot.

Secondly, when removing fungus, start with the mildest solution, and go for the hard stuff (hydrogen peroxide, ammonia) only if all else fails. This way you are not only making the process easier on your health and the environment, you are also avoiding the risks inherent to combining aggressive chemicals with old optics (where you have no idea of how coatings and lens cements will react).

First try with water.

Then move on to a very mild dish-washing solution

After that, use saliva (I’m not kidding. Saliva contains enzymes which exist to break up biological stuff such as fungi).

Only if those fail, use hydrogen peroxide (3% solution) or diluted ammonia

I have not yet had to go beyond saliva. For instance the Pentacon lens pictured above cleaned up nicely with only dish-washing solution with no ill effects to either lens or coatings And it would only have taken me 15 minutes, except that there was some oil on the blades which I decided to address at the same time.

But there is a potential issue with using saliva, namely that it contains fungie-food, so re-using that dish washing solution after having treated the fungus with saliva is sensible. Also, unless you live in an area where the tap-water is practically devoid of calcium, remember to always rinse lens elements with demineralised water (the stuff your tumble-dryer produces works) as your least step, as that way you will not leave rings after drying.

But remember. Do not try this at home unless you feel confident of being able to do it (or want to try it on a throwaway lens).

Read more:

Previous article: Part I: Oily blades

Next article: Part III: Haze