Pekka Buttler (Updated November 2025)

Introduction

Have you ever looked at items on sale on eBay (or other platform) and encountered the phrase oily blades? In this post I will tell what oily blades are, what causes them, as well as discussing their ill effects, both immediate and long-term. Lastly, This post will mention why oily blades might not be the end of the world, and what can be done about them.

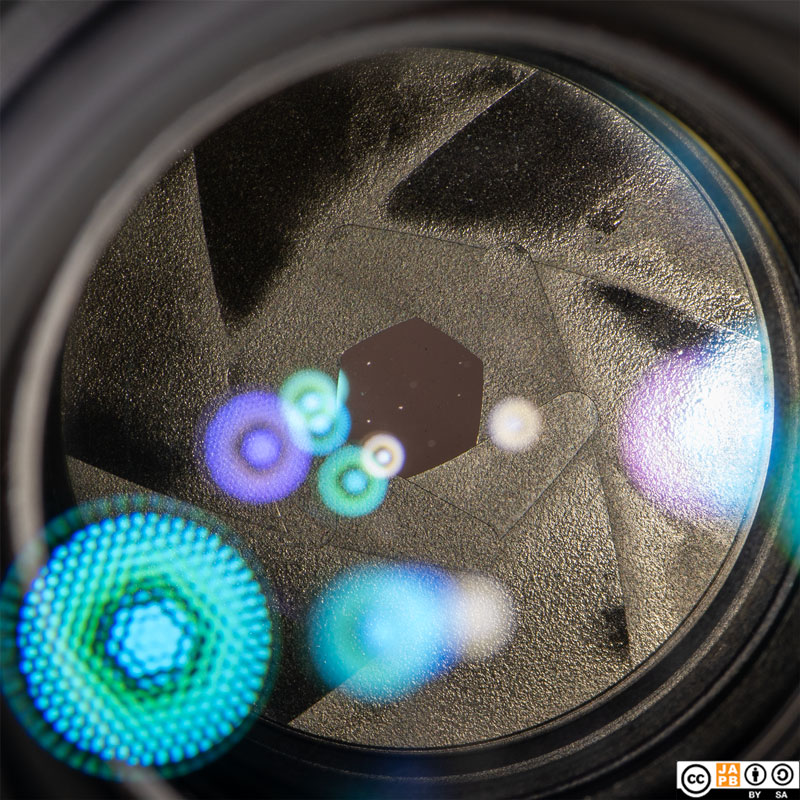

(Photographed on a Sony ⍺7R2 with a Nikkor AF-D 105/2.8 Micro lens)

What are oily blades?

Photographic lenses (as well as enlarger lenses) have an adjustable diaphragm, that offers a broad range of controls to the photographer. That aperture is typically constructed using a set of thin metal blades that can move in a way which allows them to close down the aperture.

Today, these blades are typically painted matte black to minimise reflections, but especially in older lenses the blades might also have a metallic finish. Thanks to their thinness, smoothness and shape, these blades are able to slide against each other with barely any friction.

Oily blades refers to that some lubricant has managed to reach the blades, and has spread out to cover the blades partially or entirely.

Why are oily blades bad?

In short, oily blades increase the friction of the aperture mechanism. As long as the issue is mild, it will only lead to a lame (sluggish) aperture, but it might progress to the point where the aperture becomes effectively stuck.

Let’s have a little more detailed look.

Since the advent of auto aperture lenses (more than half a century ago), the idea has always been that the aperture is fully open to aid in focusing and composing, and the aperture is closed down to whatever value the photographer has chosen, only a fraction of a second before the film (or today, sensor) will be exposed to the light passing through the lens.

In practice, this means that even though you set your nifty fifty to f/8, the aperture physically is held at fully open by a tug of war: A spring in the lens, that wants to close down the aperture as far as it goes (basically, to the selected aperture value), and a lever in the camera’s end of the lens mount that keeps the lens open to aid in focusing and composition. Of these, the camera is designed to be far stronger, thus negating the force of the spring inside the lens (n.B! With some camera mounts, the role is reversed, i.e. a spring is holding the aperture open, while the camera depresses a pin or lever to close down the aperture). You can read more on this difference in this JAPB article.

But when the photographer depresses the shutter, a lot of things start happening very fast: the camera raises its mirror, and releases the lever (thereby allowing the spring in the lens to pull the aperture closed), and actuates the shutter. All these things have to be timed very precisely, because there’s no sense in exposing the film/sensor if the lens has not yet fully closed down, or if the mirror is not yet fully raised. While cameras can be constructed to make sure the mirror is raised before the shutter is actuated, most cameras are not designed to be able to check that the aperture has closed – instead cameras tend to rely on timing: waiting a bit longer than what the manufacturer specifies as the time in which an aperture must be able to close from wide open to minimum aperture.

Oily blades are bad, because the blades are designed to have low friction when dry. A mild amount of oil (and especially low-viscosity oil) on the blades can certainly be visible, but without leading to a discernible increase in friction. Yet.

The main problem with all fluid lubricants is that they are not eternal. Even the most stable fluid lubricants have a tendency to – given time – degrade, either through volatilisation1 (think of it as evaporation, except with oils), oxidisation (reacting with oxygen), thermal cracking (splitting of long hydrocarbon chains into shorter chains) or additive depletion (neutralisation of additives through heat or contamination). Therefore any high-viscosity (light) oil will in time become a low-viscosity (thick) oil.

Oil on the blades can therefore – depending on the severity of the issue – be at a minimum a warning of a future problem (as long as the oils have retained their viscosity); be an issue that acutely affects the lens’ ability to perform as designed (when the oils make the aperture lame / sluggish); be an issue that leads to an effectively stuck aperture diaphragm (when the oils have dried to the point where the mechanism’s forces are insufficient to move the blades). We’ll return to this classification in the ‘Diagnosing’ part.

What causes oily blades?

The shortest possible way to explain oily blades, is that “oil” (lubricant in fluid state) has traveled from parts of the lens where it should be to the aperture mechanism (where it should not be).

In slightly more detail: Every lens has parts that need lubrication. Most important among those parts needing lubrication is the focusing helicoid (the mechanism that turns the rotational motion of a lens’ focus ring into linear movement of some or all of the lens elements), but also other places need lubrication (basically, wherever metal or plastic parts are meant to move respective to each other), either to guarantee a fluid motion, or simply to minimise wear and tear.

The problem with lubricants is, that in order to be able to work, they need to be fluid enough2 to be able to lubricate, and they need to retain that fluidity over a wide range of temperatures. Even though the lubricants generally recommended for optical assemblies are among the more thermally stable, the general rule is that viscosity increases with rising temperature. When temperatures rise sufficiently, even the most thermally stable lubricants tend to increase in viscosity and become increasingly affected by forces like gravity. To put it bluntly, lubricants start running from where they’re supposed to be to other parts of the lens.

While most lenses are designed so that the aperture mechanism is not in direct contact with lubricated parts, the degree of distance between lubricated parts and the aperture mechanism varies (which is why some lenses are more liable to get oil on the blades). Also, the more lubricant is originally used in the assembly (or CLA – cleaning, lubrication, adjustment) of a lens, the shorter the time before it reaches the aperture (and other undesired areas).

Having cleaned the blades on a number of lenses, all those lenses (that I have encountered) suffering oily blades have either been seriously over-lubricated or have had a design feature significantly shortening the “jump” from lubricated areas to the aperture mechanism.

Diagnosing oily blades:

Spotting oil on blades:

The phenomenon is quite often clearly visible, as the oily film on the blades clearly changes the reflectivity of the aperture blades, making the blades look darker (or lighter, depending on blade coating) where there is oil on them.

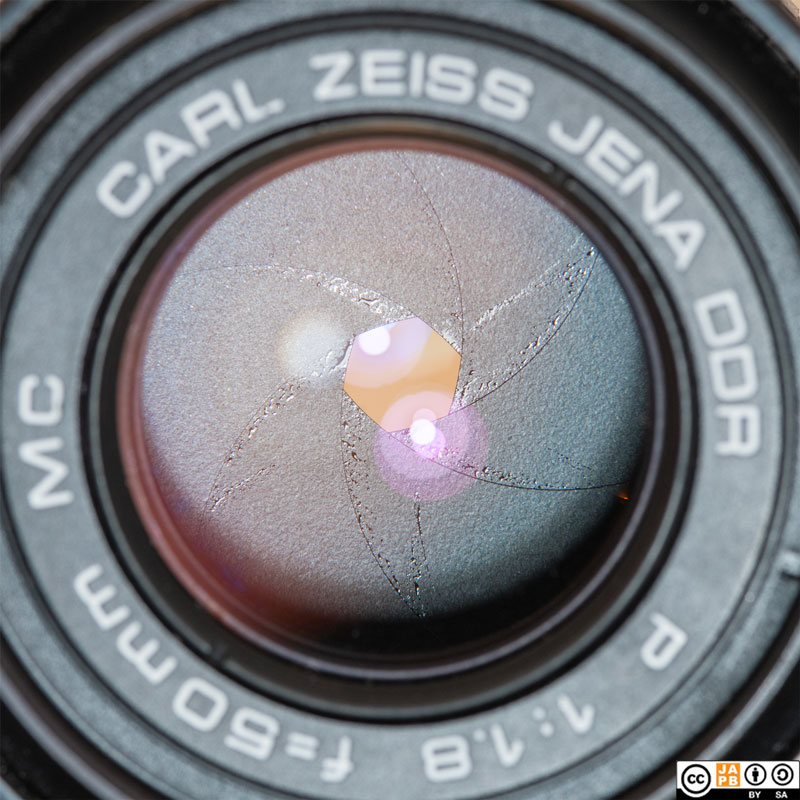

Photographed with Sony a7R and Micro Nikkor AF-D 60mm f/2.8 @ f/8

The picture, however, illustrates one important aspect of oil on the aperture blades: It is not always easily visible. The phenomenon may not show up on all aperture settings (in the case of this lens, it is most visible between f/4 and f/8), and being able to spot it usually necessitates good light.

Also, the smaller the aperture (visibly) is, the harder the problem is to spot. Therefore one should look closely with wide-angle lenses (as the lenses in front of the aperture make the aperture look smaller), and with long tele lenses, when the aperture is buried deep inside the barrel, a flashlight helps. I have also once encountered an aperture, where oil was only visible from behind, so look at the aperture from both ends.

If you’ve found oil on the blades, the next thing you should do is ascertain the seriousness of the issue. The simplest way is to test the motion of the blades using the lens’ stop down lever/pin and look (or feel) for signs of sluggishness and resistance.

Oily blades – no discernible effect on motion of aperture or exposure:

This is not an issue that warrants an immediate intervention, but does indicate that something will have to be done sooner rather than later. Also, as lubricant on the blades is both very close to lens elements, and is furthermore in the light-path, the risk for lubricant volatilisation and subsequent lens hazing should not be discounted.

Oily blades – aperture sluggish but working

At least as bad as the above-mentioned, but how much worse depends both on the type of lens and body.

If you’re using the SLR lens in its intended environment (a fully compatible SLR), your exposure’s correctness depends on that the aperture is not sluggish. In such cases, oily blades are bad, and should be fixed soonest. If you nevertheless have to shoot with the lens, you can use the DOF-preview-button or lever to stop down the lens before pressing the shutter (you need to let the aperture enough time to close down).

If you’re using the SLR lens adapted on a mirrorless camera, a sluggish aperture is not a big issue, as metering and shooting is anyhow done closed down. Mind you, the issue can only get worse, and deserves addressing.

Oily blades – stuck aperture

Unless the aperture is stuck at the very aperture you’re always using, the lens needs immediate attention.

Furthermore, you should be aware that there are some situations in which using a lens with a stuck aperture can contribute to damaging your camera. This is especially the case in lens mounts where the camera actuates the closing down of the aperture (e.g. Canon FL, Canon FD, Fujica X, M42, and many others) as whatever lever or paddle is pushing on the lens’ stop-down lever or pin is effectively running into a brick wall every time it encounters a stuck aperture.

Mind you, that an aperture being stuck may be caused also by other issues than oily blades, such as a broken coupling between aperture mechanism and aperture ring, or an aperture blade that has bent (thus, precluding normal movement). In any case: time for an expert to have a look at the lens.

Aperture sluggish, but no sign of oil on the blades

In this case, it might be that there is no oil (or other problem) on the blades, but that the misbehaviour is caused by a broken or lame spring (and is treated separately here)

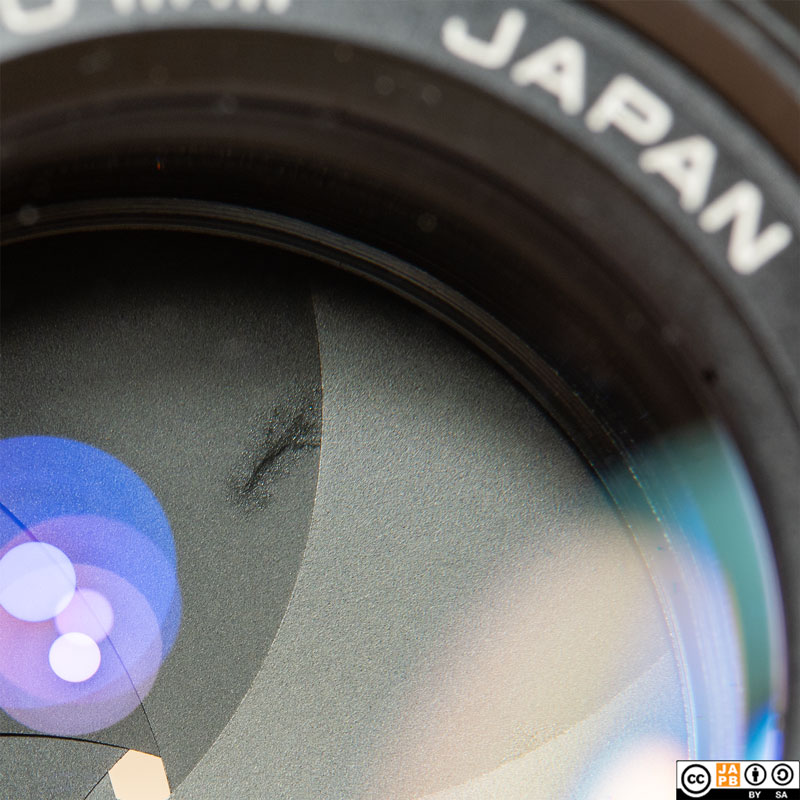

Dirty-looking blades that do not seem ‘wet’

Sometimes you will encounter aperture blades that have a clear discolouration3, but seem dry. Those discolourations can be the result of oils that have entirely dried (evaporated) and only left a residue behind, or sometimes they can also be caused by friction marks. In such cases lenses should be assessed based on whether the discolourations seem to effect the lens’ usability

Photographed with Sony a7R and Micro Nikkor AF-D 60mm f/2.8 @ f/8

When to address oily blades, and how?

Whether to hurry with having the lens cleaned depends on a combination of factors, especially: how much the oil affects your shooting; whether it’s a lens you depend on; and whether it simply might be more economical to buy a new lens.

Considering that lens mechanics’ rates vary widely throughout the globe, I won’t hazard a guess on what it will cost. Suffice it to say that accessing the aperture typically necessitates the removal of all lens elements (for the mechanic to get at the aperture) and may necessitate disassembly (and reassembly) of the aperture mechanism. Therefore, it will NOT be among the cheapest of operations. On the other hand, it typically does not necessitate spare parts, and it needs no ultra-special tools, jigs or chemicals (unlike, say, re-cementing a doublet). By nature this is an operation any proficient lens doctor can accomplish.

Alternatively, you may choose to treat the problem yourself.

Some repair tips

WARNING: This is not a lens repair blog, so I will not give you details on the task. Also, unless you have some experience of lens repair and an inkling of what the task entails, either take the lens to a professional, sell it to someone more repair-adept (remember to disclose the lens’ failings), or relegate it to your display cabinet.

There are, however, two tips I will disclose about cleaning aperture blades:

Firstly, unless patience is your middle name, and you are known for a steady hand, try to avoid having to disassemble the aperture. Work with a suitable solvent4 and a Q-tip to remove oil of the blades. You can also drip solvent straight on the blades, and jiggle them back and forth, but remember that the solvent does not remove the contamination, it just makes it more easily removable, so you will need to brush off the gunk with something. You will need to be doing this for some time, but you’ll typically be able to remove enough oil to be able to claim success. Also – with some lenses the aperture mechanism is entirely removable – you may consider popping the entire mechanism into solvent, and finish off by polishing it with a Q-tip. Make sure no fibres remain on the aperture.

Second, before you put the lens back together, let it breathe and dry out. While solvents evaporate rapidly, solvents between blades take a while to evaporate entirely, and just as you do not want oil to evaporate between your lenses causing haze, you also do not want solvents to remain inside the lens.

Read more:

Next article: Part II: Fungus

Footnotes

- Volatilisation of lubricant oils has a further negative effect in that it is the primary cause of haze in a lens (Lubricants that have become volatile and have then come to rest on lens element surfaces). ↩︎

- Note: there are dry lubricants like graphite powder, but those can be even more problematic in optical lenses. ↩︎

- N.B! Especially with old manual, rangefinder and preset lenses, you may encounter visually oil-like patterns on your aperture blades. With these lenses, there are two things to consider. Firstly, it may not be oil at all (you need to break open the lens to make sure), but simply friction scarring due to age, less advance materials science, and increased friction due to (typically) higher blade-count. Secondly, given that the aperture in such lenses is always operated by human muscle (never a flimsy spring), the issue is never as bad (unless you think you can feel the oil increasing resistance) as with any sort of auto lens. Again, if what you see really is oil, it can – given time – contribute to lens hazing, but (to be blunt) if your 50+ year old lens has not started hazing yet, there is little reason to think it will start doing so soon (and definitely no rush a repair). ↩︎

- The typical candidates are isopropyl alcohol, white spirit, lighter fluid. In general I always start with the milder solvents (IPA) and work towards the more risky solvents (lighter fluid) only if need be. ↩︎