Pekka Buttler (Updated November 2025)

Introduction

‘Haze’ – sometimes also referred to as ‘fog’ – is one of the words you often see in ads for nth hand lenses, and this article will have a look at what haze is, why it exists, how serious it is, and what can be done to clean a hazed lens. But first, we’ll need to learn how to identify haze.

What is lens haze and how does it come to be?

In the case of haze, it makes sense to explain the defect in tandem with how haze comes to be, because one helps explain the other.

A lens is – even in the best of cases – not just a combination of different kinds of solids, such as metals and glass, but also necessitates various semi-solids, such as grease/lubricant as well as other materials which are chemically not entirely stable (within the intended operating range of a photographic lens), such as balsam, lacquer and glue.

Haze forms when these semi-solids and other volatiles (more precicely: compounds containing volatiles) become volatilised or outgass, to later settle and solidify (or semi-solidify) on the surfaces of lens elements (naturally they may settle anywhere in a lens, but our main concern is that they settle on lens elements).

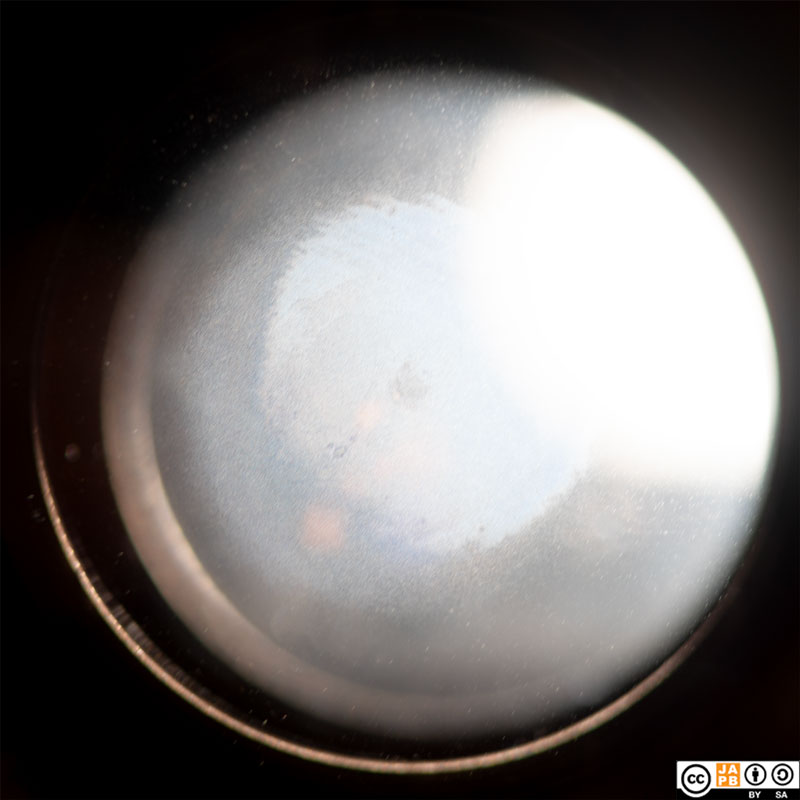

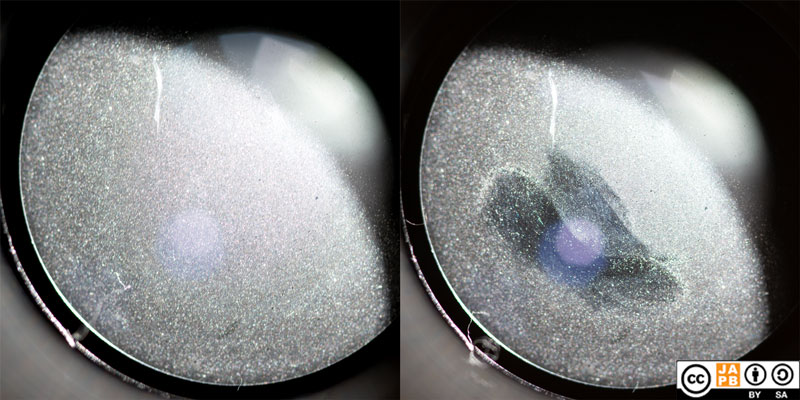

n.B! Light haze can be difficult to see by looking through a lens, but when looking through a backlit lens (small flashlight), the haze becomes obvious. This particular lens was so heavily hazed, that it was obvious even when looking through it in the relatively dim light of the post office

Hazing may thus be caused severally:

– The lens construction utilises a semi-solid compound that is reasonably stable within the designated operating environment, but the lens was forgotten in the sunlight on the patio table/car in sun/sauna, thus raising the temperature of the lens (including the semi-solid) far beyond the operating specifications. Resultingly, the semi-solid has partially evaporated and will settle on various surfaces through condensation as the lens cools down.

– The lens contains a semi-solid or compound, that is included in the lens based on the belief that it will remain stable for a significant timespan. This belief turns out to be unwarranted, and as the lens becomes older, volatiles start to outgas from the compound, settling on other surfaces.

– The lens has been inexpertly repaired, using a lubricant (or other compound) that is not suitable for the designed operating conditions or is not stable over time.

Finally, while the mechanism is somewhat different, also grease-smearing is similar to hazing (especially regarding the prognosis). Grease-smearing occurs, when the lens has been manufactured (or repaired) using either too much grease, or a grease that is not thermally stable, leading to that the grease slowly ‘flows’ from its original area onto other areas (including lens element surfaces).

How to identify haze?

First off, whether you’re browsing photo forums or youtube videos, there are a lot of people who either cannot or do not want to distinguish between haze (this article), fungus (the previous article), or element separation (the next article). The distinction is nevertheless worthwhile, because the diagnosis has significant effects on the prognosis.

How to tell haze from fungus or separation? When you get down to it, it’s relatively simple: whereas a fungus always has an organic, dendritic or fibrous structure, haze looks like mist or a misted or smeared glass. Depending on the droplet size and density a haze is made up of, those droplets may be easily distinguishable with the naked eye, or the element may just look misted over. Finally, in some cases the element may be so heavily contaminated with haze, that it looks like someone had spread grease on it and wiped at it halfheartedly. Also, there are relatively rare cases (of total element separation, see next article) where element separation may be hard to distinguish from haze.

How serious is lens haze?

When considering the severity of haze, it is sensible to separate the effects haze has on

1) the usability of the lens as an instrument of photography;

2) the repairability of the lens; and

3) the resale value of the lens.

Haze, and its effect on taking photos depends on several factors, mainly amount of haze, droplet size and dispersal, and the opacity of what the droplets are made of. There is therefore no clear answer, instead you will have to use the lens and ascertain the severity. Also keep in mind that haze will probably have a greater effect when shooting in backlit situations.

I’ve shot with mildly hazed lenses, without being able to discern a difference in before&after shots. On the other hand, some lenses have so much haze that it has a clearly discernible effect on pictures. For instance, the Tokina macro pictured above suffered a mild loss of sharpness and a massive loss in contrast (it was somewhat as if all pictures had been taken on hazy/misty days).

Obviously, you’d rather have a lens without haze (than one which is even mildly hazed), but the results may not be all bad. Considering that old-time photographers used to smear their lenses with grease or vaseline to make their models look better or more ethereal (see here or here, or elsewhere), even a heavily hazed lens might have its uses. (I had acquired the Tokina mentioned above for macro work, so I cleaned it, but it would have made a nice lens for ethereal portraits as it was.)

How about if you do not like the effect, and want to have the lens repaired? We’ll get back to that in more detail below, but the big question is: which chemical substance has evaporated/outgassed and condensed on the lens elements? Unless you know that, you will not know whether that substance is lying there on the lens element in a liquid or semi-solid state, or whether it has solidified and stuck there (making removal harder and more risky). Also, as long as you do not know what that substance may have done to the surface and coatings, severity cannot be ascertained with any likelihood (not to mention certainty).

And it is due to that uncertainty, that the resale value of a hazed lens takes a significant tumble. I would generally not recommend to buy a hazy lens at anything above 25% of going rate. This is not because haze would be unrepairable in the majority of cases, but because I have a healthy (admittedly, an unsubstantiated opinion) skepticism and assume that the lens might be on sale because the previous owner has already tried to have it repaired (and failed).

What can be done about haze?

As you already guessed if you read the previous two paragraphs, the repairability of haze depends entirely on the chemical makeup of that haze. In the best case, haze is easy to remove (or, as easy as anything that necessitates gaining access to the lens elements), and in the worst case, haze can be almost unremovable. Almost, because a highly proficient lens technician with access to the equipment needed to grind and polish optical lenses can naturally grind away even the most stuck materials, but in order for that to be an economically sensible choice, you’d need to be dealing with a very special lens (those which usually go for multiples of thousands of dollars/euros).

A competent lens mechanic may nevertheless be able to give you a quote on cleaning the lens based on their earlier experience with lenses of same era and manufacturer (remember, lenses of the same type probably haze similarly). It will not be the cheapest of repairs, but neither will it cost a kidney or your firstborn. Even so, if the lens is just a run-of-the mill nifty fifty or basic zoom, it will probably not be economically feasible to have the lens repaired by a professional.

Alternatively, you may choose to treat the problem yourself, but as I keep re-iterating:

Some repair tips

WARNING: This is not a lens repair blog, so I will not give you details on the task. Also, unless you have some experience of lens repair and an inkling of what the task entails, either take the lens to a professional, sell it to someone more repair-adept (remember to disclose the lens’ failings), or relegate it to your display cabinet.

That said, if you want to have a go at it, my recommendation is that if you reach the affected lens element(s), and cannot remove the haze with soaking in isopropyl alcohol or white spirit and gentle wiping, you either abandon the task, or continue out of morbid curiosity (knowing that you will probably do more damage than good).

Read more:

Previous article: Part II: Fungus

Next article: Part IV: Element separation