Welcome to part 2 of the JAPB comparison of nine fast 35 mm focal length lenses.

This is a big article, which has been subdivided into several parts for convenience and the sake of humane loading times. See table of contents below.

• Part 1: Introduction, the lenses: pedigree and handling

• Part 2: IQ-comparison I – The Brick wall test (you are here)

• Part 3: IQ comparison II – Urban vistas

• Part 4: IQ-comparison III – Bokeh and feel

• Part 5: IQ-comparison IV – Night-time vistas

• Part 6: Summary and conclusions

Image quality test – some remarks

And now for the part you all have been secretly waiting for <grin>. As mentioned, one attraction of the 35 mm lens is its potential for being versatile. Thus the scenes used (shot) in this comparison will attempt to encompass many of the types of real-life scenarios which you would typically use a 35 mm lens for, with one significant exception: people-shots.

This comparison was initially conducted in 2020, which will probably for some time be remembered as the Year of Corona/COVID. While my local conditions did not involve a lock-down or mandatory social distancing, the timing of the comparison made the inclusion of people shots somewhat hard. Once we reach a new normal, the comparison/review may be appended with such shots.

Oh, and one more thing: The comparisons you see below are excerpts. The entire material (10 GB in JPEG files) may be made public that day when hosting &bandwidth become affordable. Until then, if you want to scrutinise a RAW-file, drop me a line.

The ubiquitous brick wall test – close-range sharpness, distortions etc.

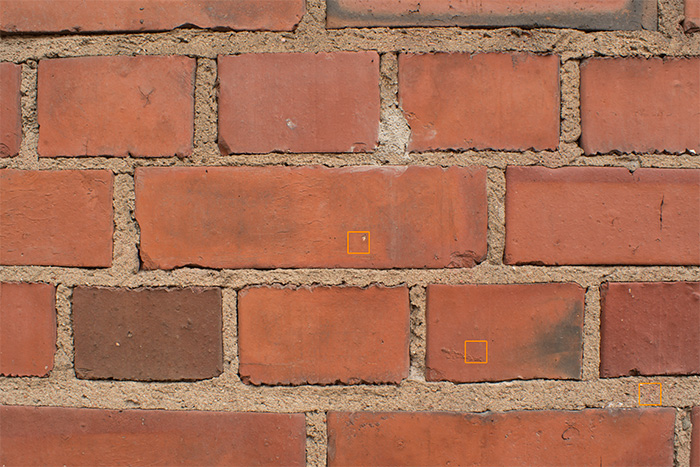

Let’s get this out of the way, before we get to the ‘real’ pictures. As pathetic as it is to set up your tripod in front of a blank brick wall, the brick wall test has its uses: not only is it a decent gauge of distortions (only decent, when your brick wall is the result of human masonry), but it offers a good test for close-focus centre sharpness-potential as well as some inkling of the lens’ corner sharpness and field curvature.

Furthermore, compared to your typical real-world shot, the brick wall test does away with some pesky nuisances, such as high-contrast transitions and varying distances to the objects (which we’ll get to in the next part)

Before you look at the 100% samples, please remember that these pictures are both an ideal case (tripod=>longer exposures & low ISO, no shake), and deliberately brutal: at 100% zoom, the real-life size of these (huge) Sony a7R2 files is roughly 2 meters by 1,3 meters.

Short note: All lenses were quickly examined for de-centering by comparing the detail evident in the mortar at the respective corners (at f/2.8). Nothing significant was found.

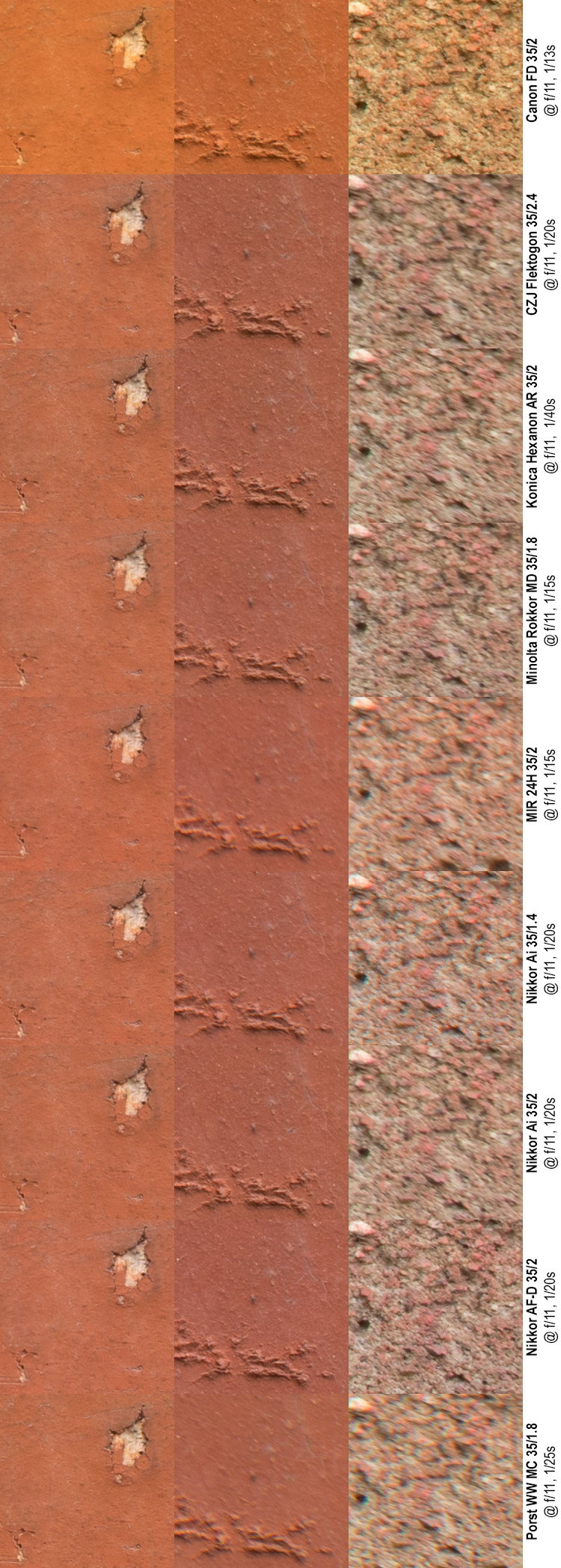

f/11

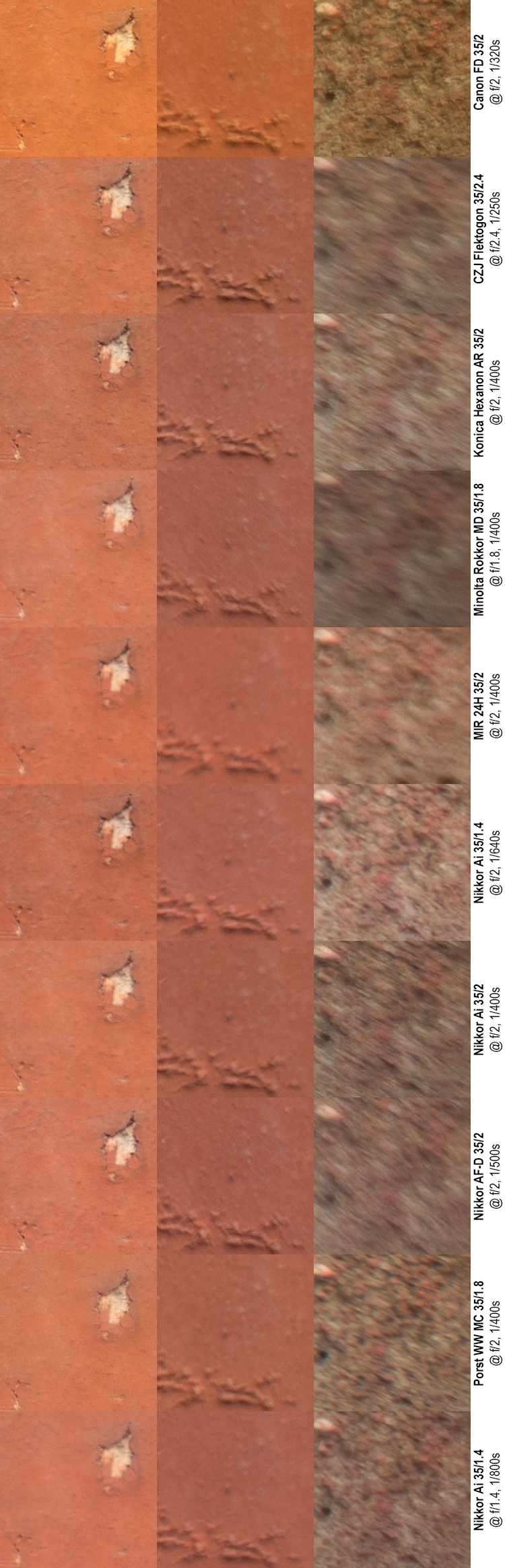

First, we’ll look at maximum across-the frame sharpness by having a look at f/11.

You have eyes, so I’ll let you scrutinise the shots to your hearts’ content, but I’ll make a few remarks:

First, and as you will notice throughout, the thoriated (and decayed) lens elements in the FD35/2 do indeed have a significant effect on colour balance (all shots are at WB cloudy (5300K)). This is not something which is irrecoverable as you can relatively easily adjust WB and tint in post to reach something very similar to the others, but I want to show you the effect ‘as is’ in these tests. You can read more about this effect here.

Second, at f/11 all shots are sharp in the image center, with only minor differences (in fact, with some of these lenses peak center sharpness is before f/11).

Third, likewise obviously, all lenses but the MIR and the Porst are tack-sharp off center (second column), while even these lense have more than enough resolution for a decent-size blow-up (at least for a magazine spread). So far, pretty much as expected.

Fourth, in the extreme corners, things are not looking as good – again no surprise – and those lenses which struggled off-center (MIR and Porst) are certainly in the worst shape in the corners, but the rest of the field is also not entirely uniform: Also the Nikkor (Ai) 35/2 and Hexanon 35/2 are struggling a bit. Relatedly, the shutter speed recorded for the Hexanon indicates that its f/11 may in fact be closer to f/8 (whether this is by design, due to sample variation or due to my inexpert repairs, I can only guess). The key takeaway though is, that at f/11, all these lenses have more than enough resolving power for significant enlargements. How about wider open? How about at f/5.6?

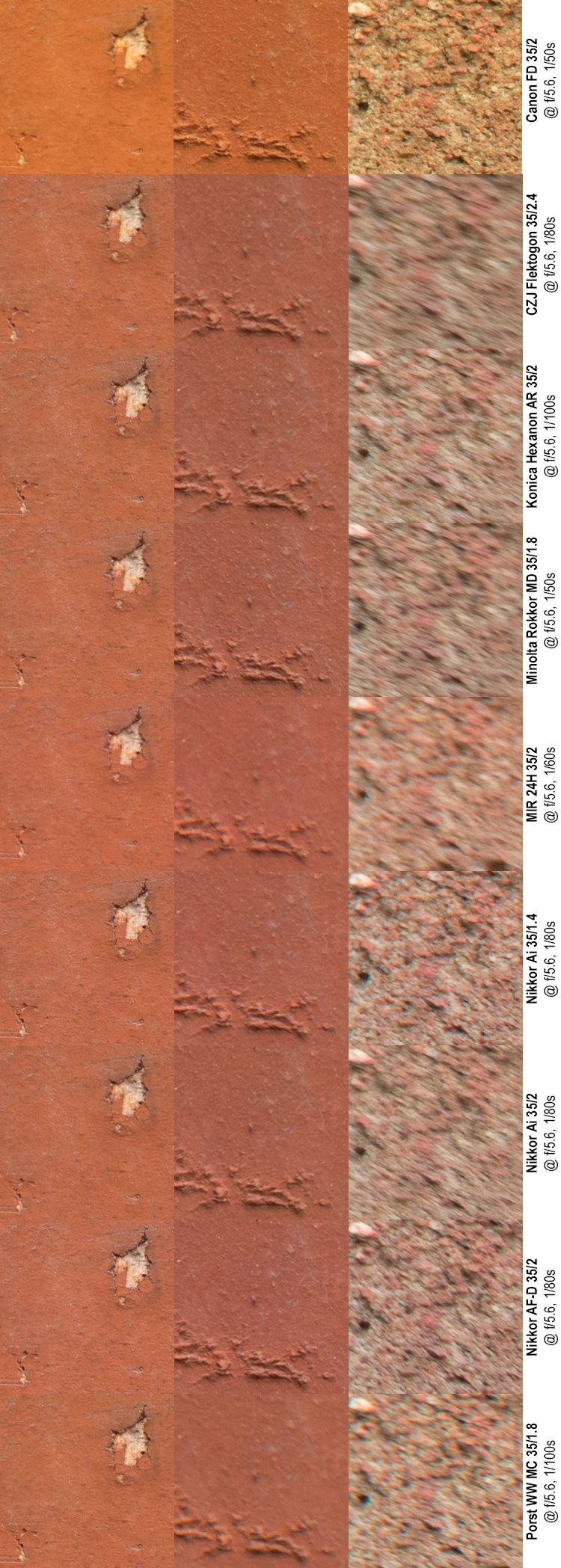

f/5.6

Let’s face it: unless you have a tripod handy, or are willing to use high ISO (and deal with noise), f/11 is not always feasible – it would not have been in this lighting (even with IBIS, 1/15s is pushing it). But even in cloudy daylight, f/5.6 should be doable. Thus f/5.6 is a somewhat more realistic aperture for hand-held shooting.

Firstly, center sharpness remains excellent throughout, and although a keen eye might spot minor differences, these are not real-world relevant.

Secondly, off-centre the situation is largely the same as at f/11, except worse. The Porst and MIR are clearly behind the pack, while the Canon, Konica, Minolta, and two of the Nikkor’s sharing the glory (the Nikkor Ai f/2 and Flektogon are somewhere in between).

Thirdly, in the extreme corners, there’s something interesting happening. The MIR is clearly struggling, but the Flektogon is not performing well either. Moreover, the Minolta 35/1.8 shows its first signs of weakness, joining the Nikkor Ai 35/2 on the second lowest tier. The Porst, which did not convince even at f/11 is making a suprisingly decent impression here, roughly on par with the Konica. The Nikkor AF lens is making a surprisingly good show – considering it’s a six-element design – but does not quite match the level of its brighter second cousin (the Nikkor 35/1.4), while the Canon FD 35/2 shows absolutely stellar performance.

Furthermore, several of the extreme corner samples are showing signs of smearing, i.e. micro-patterns being elongated away from the image centre. This smearing may be caused by astigmatism, field curvature or even comatic aberrations (or any combination of these), but determining the exact cause from test shots is sadly not possible.

Still, in many situations even f/5.6 is an unafforable luxury, so let’s up the ante and open up another few stops.

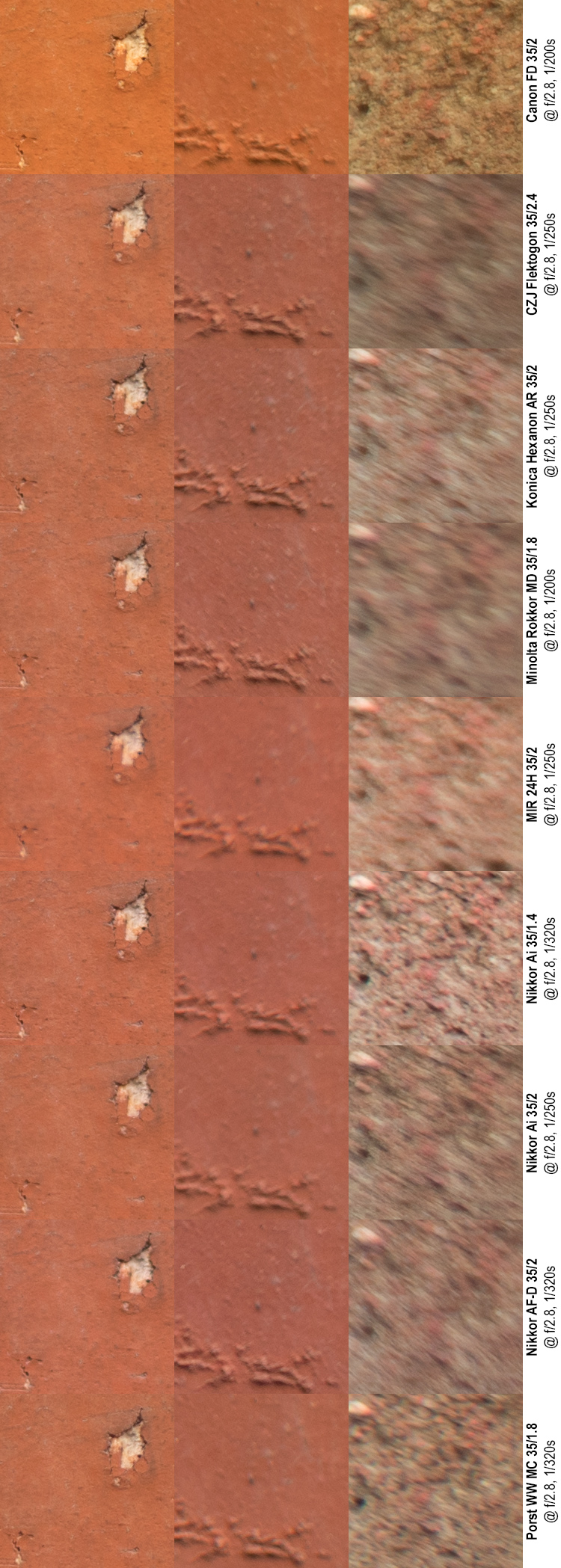

f/2.8

f/2.8 is not what you’d call a safe choice, but it is ‘stopped down’ for all of these lenses (1/2 stop for the flek, 2 stops for the Nikkor 35/1.4), so you’d be justified in expecting most of the excesses inherent to shooting ‘wide open’ to have been resolved. Let us see.

Now, things are getting tense. Firstly, we are now seeing the first unequivoal signs of vignetting in the corners. The effect is most pronounced with the Flektogon, The Minolta and the two f/2 Nikkors, followed by the Konica, and the Porst. The MIR and Canon show less signs of vignetting, while the Nikkor 35/1.4 has an obvious advantage in this comparison and makes good use of it.

Secondly, we’re starting to see clear differences in centre sharpness, with the f/1.4 Nikkor taking the lead, followed by the Konica. Porst (!), Minolta and Canon make up the second tier, followed closely by the Flektogon and the Ai Nikkor f/2. The AF Nikkor comes second last, trailed by the MIR in last place. The same story is largely repeated in off-centre samples.

In the corner, the Nikkor f/1.4 and Canon share the top spot, followed by the Porst. The rest show various degrees of heavy smearing, and putting them in any order is more an exercise in the application of taste than anything even approaching objectivity.

But as the point of large-aperture lenses is to allow low-light and/or narrow depth-of-field photography, this comparison would be grievously incomplete without wide-open samples. So let us…

wide open

Firstly, please note that the Nikkor 35 mm f/1.4 has two rows of clips here: one in its customary position, as well as a second one @ f/1.4 at the bottom. We’ll get back to the Nikkor at f1.4 later, and focus on the f/2 (-ish) shots for now.

Vignetting tells largely the same story as at f/2.8, except worse. The Minolta suffers very badly, with the Flek and the f/2 Nikkors sharing second worst. Canon, Konica, MIR and Porst fare much better, but all are upstaged by the f/1.4 Nikkor (which is not wide open, yet).

Looking at centre sharpness, it is obvious that all lenses suffer some degree of spherical aberration when wide open, leading images being somewhat dreamy (typically the definition is there, but contrast is lacking). This can most clearly be seen when comparing an f/2.8 shot with a f/2 shot, but even so, levels of dreaminess can be discerned: at f/2 the f/1.4 Nikkor runs circles around the rest of the field, with only the Hexanon putting up a challenge. The second tier is composed of the Canon FD, the Flektogon (@ f/2.4) and the AF Nikkor. The remaining four are nothing to write home about, except that the Porst, MIR and Nikkor Ai f/2 manage to squeeze past the Minolta, albeit very marginally.

Off-centre the story is somewhat different, especially as the f/1.4 Nikkor is not making waves here. Instead, the top-3 are composed of the Canon, Hexanon and Flektogon. Also suprisingly, the Minolta (which did badly in the centre) manages to resolve a lot of detail, albeit with relatively low contrast. Likewise the AF Nikkor manages to reproduce detail, even though the picture shows obvious beginnings of smearing. The remaining two Nikkors and the Porst also manage to resolve details but with a significant loss in contrast (a combination typically caused by spherical aberration), whereas the MIR shows the worst loss of contrast here.

In the extreme corners, the story is again somewhat different. The FD does lose some contrast, but resolves details astonishingly well, and with no sign of dreaminess or smearing, while the Nikkor f/1.4 (at f/2) makes a good show, but is upstaged by the lowly Porst (both have obvious loss of contrast, but even though the Porst suffers more vignetting, it resolves more detail). The entire rest of the field show extensive signs of smearing, and while one could find ways to rank these samples, whether that would be useful is questionable.

Now, how about the Nikkor at f/1.4? All samples (center, off-center and corner) show signs of glow and loss of contrast compared to f/2, and while the center and off-center performance at f/1.4 is on par with the worst of the other lenses at f/2, the corner clip shows that the Nikkor’s performance in the corner is the same as at f/2 (except darker). Also, the level of vignetting shown by the Nikkor f/1.4 wide open is severe, but not any worse that it’s slower siblings (the f/2 Nikkors) at their respective wide open.

Sharp bricks – summary

In sum, this sharpness test tells the same story as 99% of all sharpness tests: Center and off-center performance is always improved by stopping down, one or two stops, while the peak performance is reached at about f/8 (center) and f/11 (off-center). Likewise, extreme corners may need another stop after that, and may – in fact – never become really sharp. That said, there are also clear differences (even in a low-contrast sharpness test), which can help make informed decisions (assuming sample variation is not excessive).

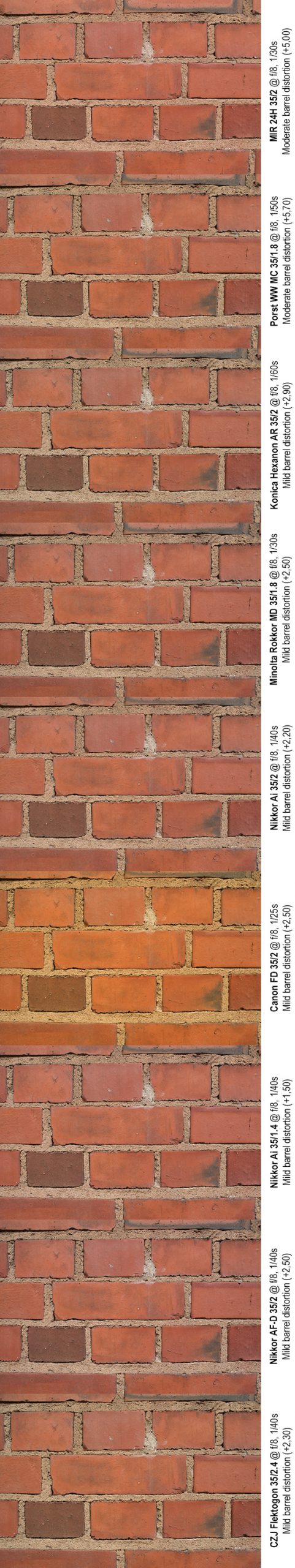

Distortion

While distortion on digital no longer is the issue it was in the age of film, it nevertheless remains a nuisance. At a minimum, correcting distortion – when relevant – is one more step in the post-production workflow. Also (depending on the detailed nature of distortion), one may need use a more forgiving framing, so that there is non-critical stuff around the edges. Finally, some lenses exhibit distortions which are not as easy to fully correct for.

In this selection, the lenses exhibited somewhat varying distortion characteristics. Admittedly, no lens had a particularly wavy distortion pattern (all could be easily corrected in Photoshop’s lens correction tool), and all lenses exhibited various degrees of barrel distortion (as expected). That said, the amount of distortion varied from barely field-relevant (Nikkor 35/1.4) to quite plain (Porst, MIR). See below.

35 mm is not necessarily 35 mm

Not all 35 mm lenses are created equal, and nowhere is this more plain in that their fields of view varied somewhat. The MIR lens was significantly wider than the rest, while the Flektogon was – by a considerably smaller margin – the narrowest. Sadly, I had not prepared for this and cannot offer precise metrics on the resulting FOV’s. Instead, the picture below superimposes the FOV of the Flektogon (Outlined rectangle) on the FOV of the MIR.

Note please, that while effective field-of-view may change as a lens’ focus is changed, the differences shown here were by-and-large similar when focused near infinity: Of the nine lenses, seven offer only minor differences in field-of view, with the MIR and Flektogon as outliers at both ends (wider and narrower).

Next… or back?

• Part 1: Introduction, the lenses: pedigree and handling

• Part 2: IQ-comparison I – The Brick wall test (you are here)

• Part 3: IQ comparison II – Urban vistas

• Part 4: IQ-comparison III – Bokeh and blur

• Part 5: IQ-comparison IV – Night-time vistas

• Part 6: Summary and conclusions