Pekka Buttler, 06/2023–

• n.B! The material for this article was gathered while I was investigating Meyer-Optik Görlitz names. As it would be a shame to keep it for myself, I will instead publish these…

• This article is not complete, in that it does not cover all interesting lens names. Instead of me waiting until it contains ‘everything’ I will publish it and add to it as I go…

• I am also making the choice not to add lens schematics to this article, as trying to summarise a key approach into one schematic would not do the design any justice (how many different planar’s or flektogons has there been during the years?).

Zeiss naming logic

Zeiss – from the prewar Carl Zeiss to the modern reunited Carl Zeiss (as well as the cold-war Carl Zeiss Jena and Carl Zeiss (West/Opton/Oberkocken) have almost (see caveats and exceptions at end of article) always had a distinct naming tradition wherein the ‘Name’ given to lenses has been a reflection of the type of optical design used.

This distinct naming logic is however marred by complications: Firstly, for a period of over 40 years there were two Carl Zeiss’ (East and West) on various sides of the iron curtain and that these two companies did not share nomenclatures – in fact Carl Zeiss (west) tried to deny Carl Zeiss (east) the right to use the traditional lens names (and largely succeeded) .

Secondly, there are cases where lenses that largely share a design have been, at different times, available under several names. Thirdly, neither Zeiss (west) nor Zeiss (east) were immune to corporate restructuring with the ensuing transfer of designs, templates and trademarks. Finally, while the classic Zeiss designs actually only apply to prime lenses, some of the names are so iconic that they’ve been freely (and with little real shared genealogy) used for zoom designs as well. The list below is not exhaustive, but covers the most significant families of Zeiss still photography designs. Also, the list omits those designs that fell out of use after WW2 (e.g. Unar, Protar).

Planar

(pre-war Carl Zeiss and Carl Zeiss West) 1896->

Standard to Tele lenses (45–135 mm FFE)

Double gauss design for SLR lenses. Originally the Planar was a perfectly symmetrical (6 elements, 6 groups) design and was developed by Paul Rudolph in 1896.

Due, however, to the many air-glass interfaces the Planar suffered significant flaring and transmission loss until the introduction of modern/pre-modern antireflective lens coatings. The Planar-design however had three inherent advantages: Firstly, due to its symmetrical/near-symmetrical design it had low distortions and an unusually flat field of sharpness (very low field curvature), hence also the name ‘Planar’.

Secondly, due to its design, it allowed (for its time) unusually large maximum apertures. Finally, the near-symmetrical design was not automatically an issue for SLR cameras as the larger focal length of standard lenses (compared with wide angles) allowed for the back focus distance necessitated by SLR’s mirror boxes. Almost all vintage and modern legacy large-aperture standard primes for SLR cameras utilize a Planar or modified Planar design.

Tessar

(Pre-war, East and West) 1902->

Standard lens (40–50 mm FFE)

The Tessar (together with the Sonnar and Planar) is one of the most famous Zeiss designs. The Tessar – another of Paul Rudolph’s master strokes – first saw the light in 1902 and was – itself – the combination of two earlier Zeiss designs. In essence, the Tessar combines the Zeiss Unar’s (4 elements in 4 groups) and Zeiss Protar’s (4 elements in 2 groups) into a relatively compact 4 elements in 3 groups design.

The Tessar design has the weakness that it cannot be used as basis for large-aperture lenses. On the other hand – especially prior to the development of modern coatings – the Tessar’s low group count means that the Tessar has half the air-glass interfaces of a Planar, and is therefore much less likely to suffer bad flaring and have better real-life transmittance. Being a relatively simple (and therefore: cheap) lens to produce made the Tessar the go-to choice for many mid-range cameras.

Furthermore, it could be implemented either as a unit-focusing lens (all elements move to change focus) or – without a significant IQ penalty – as a single-element focusing lens (by shifting the front element vis-à-vis the other elements).

A testament to the Tessar’s long-lasting fame is that the name is used extensively in lenses (e.g. Tele-Tessar, Vario-Tessar, Smartphone lenses) that share very little if anything with the Tessar design.

Sonnar

(pre-war, East and West) 1929

Standard to tele lens (rangefinders) or tele lens (SLR’s) (50-200 mm FFE)

The Zeiss Sonnar is a 1929 design by another of Zeiss’ most famous designers: Ludwig Bertele. While ‘Sonnar’ was traditionally a trademark belonging to another photographic manufacturer, that company had been merged with Zeiss, allowing the adoption of the Sonnar name for this design, which was characterized by (for its time) exceptionally wide apertures.

While initially offered as a 50 mm f/2 design for rangefinder cameras (see above), this was quickly superseded by an even brighter 50 mm f/1.5 design (see below). Moreover, even though the Sonnar has 6 or 7 elements, it cements these together in only 3 groups, leading to improved contrast and flare-resistance. On the other hand, especially with longer focal length designs, the Sonnar necessitates relatively large lens elements, thereby leading to lenses that are both heavy (and front-heavy) and costly to manufacture.

While the Sonnar design can be used for standard lenses in cameras that do not have a long back focal distance (rangefinders), on SLR’s with mirror boxes, Sonnars can only be used for tele lenses.

Triotar

(pre-war, east and west)

Short to medium tele (85–135 mm FFE)

Carl Zeiss Jena (Prewar) introduced the Triotar 85 mm f/4 in 1932 as a cost-effective and not so bright short tele for the Contax rangefinder. This lens was subsequently also manufactured by Carl Zeiss/Opton (West).

Around 1936 a 105/5.6 Triotar was introduced for the Zeiss Ikon Nettax.

After the war, Carl Zeiss Jena (East) introduced a longer version (135/4) for a range of SLRs.

All Triotar lenses are triplet designs (3 element in 3 groups).

Biogon

(pre-war and West)

Wide-angle to ultra-wide angle (20-35 mm FFE).

Originally designed by Ludwig Bertele and introduced in the 1930’s, the Biogon is a semi-symmetrical/symmetrical design used in rangefinders, as well as medium and large format. While the design is compact compared to similar retrofocus designs (Distagon/Flektogon), it allows high image quality in combination with low distortions. Due to the semi-symmetrical design Biogon lenses have a short back focal distance and can therefore not be used on SLR cameras. On modern mirrorless cameras old Biogon designs can lead to a corner color cast, as can be seen here (The Jupiter 12 is basically a reiteration of the prewar 35 mm f/2.8 Biogon).

Interestingly, Carl Zeiss Jena (East) decided to not manufacture Biogon designs, rather opting for developing a wide-angle version of the Biometar for use on rangefinders.

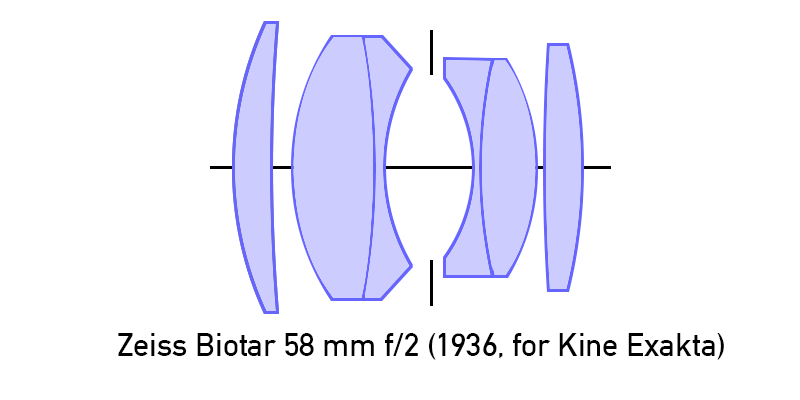

Biotar

(pre-war and East) 1939 ->

Standard to short tele lenses (58-75 mm FFE)

Also the Biotar design is a derivative of the Planar. While the Biotar was initially intended for cinematography, the design showed promise and was later upscaled to fit 35 mm film. However, while the 50 mm f/1.4 Biotar was suitable for cinematography, it did not cover 35 mm film and had to be redesigned.

The Biotar for still photography was made famous by the Carl Zeiss Biotar 58 mm f/2 lens (from the late 1930’s). While the 58 mm Biotar was in many ways revolutionary, it was initially overshadowed by the advent of the second world war, the ensuing slump in camera sales and the repurposing of the optical industries to serve military needs.

Its production was taken up again after the war, especially in the Soviet Union as the Helios-44 (58 mm f/2) lens which is one of the most (if not the most) numerously produced photographic lenses in camera history.

The Biotar design was however used also for some other lenses, among which the 75 mm f/1.5 Biotar, often referred to as the ‘King of Bokeh’.

Biometar

(East) 1948->

Standard to short tele (50-80 mm FFE) on SLRs; 35 mm on rangefinder

The Biometar was and is a rather unique design. It was originally born out of a very specific necessity, but it likely made its biggest mark in a relatively unrelated field.

The necessity? During the immediate pre-WWII years, Zeiss had two of the best standard (≈40-50 °) lenses in its lineup: the Tessar family and the Biotar family. Problematically, they both had some very specific weaknesses.

The Biotar was – with its 6 elements in 4 groups design – both expensive and difficult to manufacture. Moreover, the Biotar was originally conceived as a cinematography lens and upscaling it 35 mm film was already stretching it a bit. Hence, going to medium format would have been prohibitively expensive.

The Tessar on the other hand was a simple construction that was rather economical. Moreover, its relative lack of brightness (f/2.8 for the Tessar vs. f/2 for the Biotar) was less of a drawback on medium format. Problematically, various attempts at stretching the Tessar designs for use on medium format were never really seen as satisfactory. Furthermore, the increasing quality of film started highlighting that also the ‘eagle-eye’ Tessar had its limitations, also on 35 mm film.

What was born out of this dilemma was the Biometar: its front three elements are clearly related to the Biotar (and the double-Gauss roots), whereas the rear was a radical simplification of the Biotar, replacing the doublet with an aggressively curved dispersing lens, producing a 5 elements in 4 groups design. The design itself was finalised in 1941, but shelved due to the war.

In the postwar years the Biometar design was revived by Carl Zeiss Jena (East), and put into production. At this stage, its role had clearly become that of ‘the better Tessar’ and was mainly employed as a replacement for Tessar designs on the more ambitious medium format cameras (Rolleiflexes, as well as the up&coming Praktisix). While some enigneering samples of a 50/2.8 Biometar for 35 mm formats were made, management at Carl Zeiss Jena likely concluded that the it did not need a third option between its venerable and cost-effective Tessars and the new and promising line of improved Biotars (that were initially known as Flexon and later became the Pancolar). Hence, the Biometar design was mostly used as 80/2.8 and 120/2.8 variants on medium format, and as a 80/2.8 short tele on 35 mm film.

Mostly, because the basic approach that is the Biometar has made two further appearances. First, the Biometar made an – in hindsight – surprise appearance as a 35 mm f/2.8 lens for the Contax rangefinder. This in itself highlights the fundamental versatility of the Biometar’s design, where the angle of view is – largely – a function of the back focus distance. This – in turn – led to the invention known as the Flektogon (see below) because the original 1959 Flektogon is nothing more than a Biometar, with a large dispersing lens element added to its front.

Flektogon

(East) 1950

Wide-angle to ultra-wide angle (20-35 mm FFE)

Flektogon is not strictly one design, but a family of related designs.

The Flektogon is a retrofocus construction purposefully designed for SLR cameras. The original Flektogon 35 mm f/2.8 design was developed by Carl Zeiss Jena (East Germany) in 1950 and while some sources say that it was inspired by Angénieux’ retrofocus design, the patent applications were practically simultaneous.

The Flektogon was subsequently copied by Carl Zeiss Oberkochen (a rare case of West copying East) and renamed Distagon. The Flektogon designs were offered for 35mm as well as medium format. Due to the retrofocus design, Flektogon lenses are by necessity bulkier than their rangefinder brethren (especially at the wider end of the roster).

Distagon

(West) 1953 ->

Wide-angle to ultra-wide angle (15-35 mm FFE)

Again, the Distagon is not strictly one design, but a family of designs based on using a retrofocus construction for use with cameras that have a mirror box and thus necessitate a significant back focus distance.

While Carl Zeiss (West) initially copied the lens design from Carl Zeiss Jena (East), it is fair to say that Carl Zeiss (West) perfected the design.

F-Distagon is the designator used for fisheye lenses.

Pancolar

(East) 1962 ->

Standard to short tele lenses (50-80 mm FFE)

The Biotar had the drawback of being at the brink of not actually being a standard lens, but instead being a short tele. With the photographic mainstream in the 1950’s aiming for bright 50 mm lenses, the Biotar was selected for a redesign. That redesign (as a 50 mm f/2 lens) was originally supposed to be sold under the Biotar name but was (after an initial trial batch) renamed the Flexon. This name also remained short-lived and was subsequently renamed the Pancolar.

During the 50’s–80’s the name Pancolar (and the same fundamental optical design) was used in many variations (including 50/2; 50/1.8, 55/1.4, 75/1.4, 50/1.4 and 80/1.8). In sum, the Pancolars from Zeiss’ Jena works had a good run, up to the moment when the wall came down.

Mirotar

(West) 1963

Supertele (500-1000 mm FFE)

Mirotar is the design name that Zeiss (West) reserved for its mirror (catadioptric) lenses.

Hologon

(West) 1966

Hyper-wide angle (15-16 mm FFE)

The Hologon is a ultra-wide, symmetrical design used in rangefinders. A compact design that (due to its symmetrical design) is free of many distortions and aberrations that routinely plague ultra-wide lenses, but suffers strong vignetting. Also, the design leads to relatively dim maximum apertures (f/5.6 or f/8). “Hologon” is derived from the Greek words holos (everything), and gonia (angle).

Caveat-time:

One: After East German Pentacon introduced the Praktica bayonet mount and the new set of cameras (and lenses) to go with those cameras, they made a somewhat interesting policy decision, demanding that all Praktica B mount lenses (whether they be Pentacon’s own lenses or lenses manufactured by others) carry the name ‘Prakticar’. Hence, Carl Zeiss Jena lenses for Praktica B mount do not carry the name of the optical design. Instead, all those lenses – whether Flektogons, Pancolars, Ernostars or Sonnars are all just called “Carl Zeiss Jena Prakticar <focal length> <max. aperture>”

Two: The rule that Zeiss lens names reflect the optical design only applies to still camera lenses. For other types of lenses the name rather indicated the intended use of the lens:

• Tevidon was the name to cover the entire range (35-350 mm FFE) of C-mount and TV camera lenses produced by Carl Zeiss Jena (East);

• Dokumar lenses are reproduction lenses.

• Visionar and Kipronar are names for projection lenses from Carl Zeiss Jena (East) (Visionars were actually not designed by Zeiss but manufactured under license of Rathenower Optische Were, while Kipronars were an in-house design).

• The various series of Carl Zeiss (West & post-unification) cinema lenses never reflected the design.

Three: Recently (this millennium) Zeiss also started to sub-brand its photographic lenses according to the type of camera they were intended for:

• Otus – no compromise, manual focus, full frame lenses for Nikon F and Canon EF mounts

• Milvus – manual focus, full frame lenses for Nikon F and Canon EF mounts

• Loxia – manual focus, full frame lenses for Sony FE mount

• Batis – autofocus, full frame lenses for Sony FE mount

• Touit – autofocus, APS-C frame lenses for Sony E and Fujifilm X mounts.

Often this sub-branding would run parallel with the ‘classic’ design-based naming (leading to lens would carry both the designators “Milvus 2/35” (on barrel) and “Zeiss Distagon 2/35” (On name ring).

- I am intentionally referring to Soviet versions of Zeiss Classics as ‘remakes’, not as ‘copies’. Read the JAPB article on the Soviet Lens ‘Business’ to understand why. ↩︎

- See footnote 1. ↩︎