Pekka Buttler, March 2020

Introduction

As you probably know, the lens mount is the physical, mechanical (and, more lately, electronic) interface between a lens and the camera body. Lens mounts are a feature of system, or interchangeable lens cameras (subsequently ILCs), and must be designed with an eye towards ease of use, while considering users who are often less than 100 % diligent.

At its most basic, a lens mount serves three purposes:

- To securely attach a lens to a body,

- to do so at the correct distance (the Flange Focal Distance), and

- to make sure no light seeps through.

All lens mounts ever designed and implemented do these three things (albeit at times with varying success).

For early “system”, or “interchangeable lens cameras”, fulfilling these three purposes was all that was needed, but as camera technology progressed, new needs arose: making metering more user friendly necessitated the camera be able to read (and steer) the lens aperture; shooting modes (such as shutter priority) made the camera need to be aware of the range of apertures supported by the connected lens; autofocus needed that the camera be able to control the lens’ focusing; while several subsequent technologies (distance reading, optical stabilization etc.) necessitated further communication and power feed from the camera to the lens.

What makes a discussion of lens mounts interesting in other ways than in a purely geeky way, is the plethora of different lens mounts out there, and their compatibilities and incompatibilities. Under the heading “Why are there different lens mounts” we will inspect the three fundamental sets of reasons for the existence of such a range of lens mounts: optical, technical and economical. Under the next heading “Relevant mounts”, we will discuss what makes a lens mount ‘relevant’, and list those mounts which fit the criteria.

Why are there different Lens Mounts?

Optical reasons

Even though technical reasons could be addressed and if economic reasons could be circumvented, there would still be roughly as many lens mounts as there are film (or sensor) formats. The reason is simple: the image circle a lens produces must be able to cover the film (or sensor) area to be exposed (and do so while in focus). At its most basic, that means that the larger the diagonal of the film, the farther away the lens will have to be mounted in order for the light from the lens to not strike the film plane more or less equally and not in too oblique an angle. Resultingly, the flange focal distance (distance of the lens mount flange to the film plane) tends to be longer for bigger films/sensors.

Likewise, the flange focal distance is also affected by whether the camera is a rangefinder or a reflex camera, as the mirror in reflex camera needs some space to be able to work – a space which is largely defined by the size of the mirror. Also, as the size of the mirror (and mirror box) is largely influenced by the size of the film, larger format SLR’s tend to have longer flange focal distances.

The flange focal distance is one of the fundamental traits of a lens mount, as even if you were able to mount a lens from a different mount (stably and without light seepage), different flange focal distances would result in a combination which could not focus as close as intended, or which could not focus to infinity.

But even looking at a specific film (or sensor) format, and a single type of camera – such as the 35mm SLR – there are in fact a multitude of respectively incompatible lens mounts. To understand why that is, we need to dig further

Technical reasons

For a short while around mid 20th century, there actually was something of a common standard: the M42 lens mount (variously also referred to as the Praktica thread mount or the Pentax thread mount. The M42 lens mount is exceedingly simple both in design and manufacture: A 42 mm thread mount with a 1 mm thread pitch.

While not nearly all camera makers used this mount, many did. And not only were its users numerous, but also well spread out: Chinon, Fuji, Pentax and Yashica in Japan; Zenit in the Soviet Union and Zeiss, Pentacon in the Germanies (list far from exhaustive). And the reason for me bringing this up, is that many of those companies which had previously used the M42 mount went on to start their proprietary mounts, which makes this an interesting case to study.

The M42 mount had serious limitations. In its original form it was nothing but a screw to attach the lens, meaning that you had to first open the lens aperture up in order to focus, then close it down to the desired f-stop to take the shot. Rinse and repeat. This was addressed by a simple pin (pressed by a lever in the camera body) which closed down the aperture just prior to taking the shot. This simple screw-and-pin&lever constellation is the most common form of M42 mount and the one you’re probably most familiar with. Besides the camera makers who produced their own lenses, there was also a multitude of optics companies which produced lenses for these cameras.

But as camera bodies continued to progress, and in-body metering became increasingly common (and sought-after) the M42 mount was again under challenge. As the camera neither knew the lens’ maximum aperture, nor the selected aperture, metering could progress only through stop-down metering. First you focus (aperture is open), then you depress a button or switch (similar to depth-of-field preview on more modern cameras), to activate the lever which pressed the pin to the pre-set aperture, after which you could check whether the combination of aperture (on the lens) and shutter speed (on the camera body) were suitable for correct exposure. While certainly preferable to walking around with a light meter, this nevertheless was a hassle and camera manufacturers – always keen to extend their client base towards less and less technologically savvy users – wanted to address this.

At this stage variance started creeping in: some camera manufacturers added electronic contacts to their M42 lenses and bodies to facilitate lens-body communication, while others preferred mechanical solutions. As suddenly M42 lenses were no longer universally compatible (and these steps were indeed stopgap measures), a new lens mount was needed.

The obvious solution would have been for the camera makers that had previously used the M42 mount to gather around and decide on a new shared standard. The reason why this did not happen is largely economical.

Economical Reasons

While one could suspect that agreeing on a shared, new mount would not have gone smoothly (think of the hassle international standardization bodies face on a daily basis), there were also purely economic reasons why this did not happen.

Assume you are a camera maker, who not only wants to sell cameras, but also lenses. Given how easy the M42 mount was to utilise, the camera maker often ended up selling only the camera body (and maybe a kit lens), where after the camera owners would satisfy their need for further lenses by buying lenses from competitors or third party lens makers.

Assume further that you (a camera maker) have on the drawing board a new type of camera that will be attractive to potential customers. By launching a new lens mount for such a camera (and a set of compatible lenses), you can – at least momentarily own the market for lenses to go with your camera as well.

As a result Pentacon created the Praktica-B mount, Pentax the Pentax-K mount, Fuji the Fujica-X mount (not to be confused with the current Fujifilm X mount), and so on. While this as such did not kill off third-party lens makers – a number still survive today – the added cost of having to make lenses for an ever increasing number of mounts put a severe strain on their capabilities. Irrespective of the reasons, most third-party lens makers and sellers from the 60’s, 70’s have gone under or shifted their business to more lucrative avenues.

These economic rationales are still at work today, as is obvious from the uneasy relationship major camera makers like Nikon and Canon [1] have had towards remaining third party lens makers. Moreover, while a mechanical interface could always be reverse-engineered and emulated, electronic lens-body interfaces enable camera manufacturers to make life very hard for third party lens makers.

Relevant Mounts

Now that you know what a lens mount is, and why there are so many of them, I want to focus back down on the list of lens mounts which are still relevant today.

Given that the probable audience here are not the know-it-all pro’s, nor those who are thinking of buying a camera as a status symbol (to have adorning the living room shelf, next to their collection of antique Swiss watches), I am going to focus this discussion of “relevance” squarely at those lens mounts relevant to today’s users of interchangeable lens cameras, specifically full-frame cameras but also those with a crop factor between 1.0 and 2.0.

While your mileage may vary, I judge that there are a number of criteria which make a lens mount ‘relevant’ today. (If you disagree on the principles or my judgments, drop me a line and tell me why I’m wrong.). Therefore, in my opinion a lens mount which fulfils any of these criteria is worthy of attention:

- The principal company(companies) behind the lens mount are continuing to actively support it. Typically you can buy these cameras & lenses new.

- The lens mount – while obsolete and unsupported – has a large installed base and the lenses can be adapted to be used on a contemporary camera. These lenses (and bodies) are mostly available only at second hand.

- The lens mount – while lacking a large installed base – has some redeeming features, such as especially fine lenses or something else that makes them interesting…

In order to avoid long listings without context, I’m going to divide this discussion into three subtopics: “Current lens mounts”, “Popular legacy lens mounts”, “Interesting legacy lens mounts”.

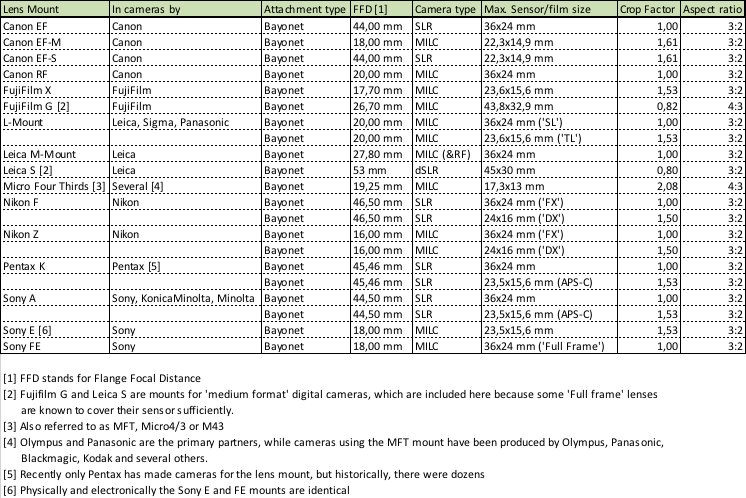

Current lens mounts

Remember, to be on this list, a lens mount has to be utilised by an interchangeable lens camera that is currently being sold. Therefore, some rather recent lens mounts are already omitted (Nikon 1, Olympus 4/3, Samsung NX, etc.) as manufacture of said cameras has ended.

Looking at that list, some things are obvious. Firstly, the big-three (Canon, Nikon, Sony) are well represented, while Fuji, Leica, Olympus and Pentax are also present. Likewise, it is obvious that several mounts exist in both ‘Full Frame’ and APS-C formats. Also, the Micro Four Thirds format stands out somewhat – both due to its higher crop factor, and due to its different aspect ratio.

Most prominent though is that all mounts designed for mirrorless (as well as the Leica M mount) have very short flange focal distances (FFD) compared with those mounts designed for SLR cameras. This has major implications, should you want to adapt lenses from one mount to another, as adapting a lens from a mount with a longer FFD to a body with a shorter FFD is immensely more simple.

Then, there is also a dichotomy of sorts: While a majority of these mounts are quite new (introduced after 2008), there are also some Methuselah’s around: The Leica M mount (introduced 1954), the Nikon F mount (1959) and the Pentax K mount (1975).

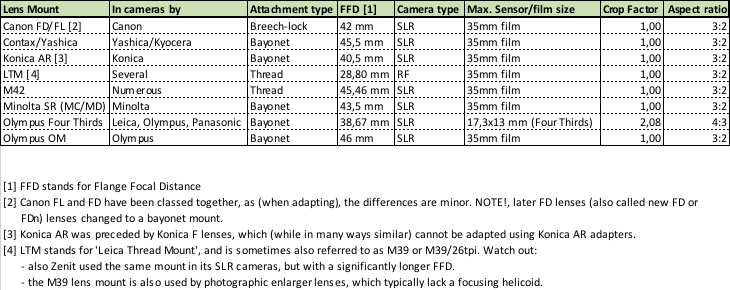

Popular legacy lens mounts

As some of these mounts are less familiar, some comments are called for.

Canon’s FL was not Canon’s first proprietary lens mount, and was quickly superseded by the Canon FD mount. FL lenses could nevertheless be used on FD bodies. The Canon FL and Canon FD mounts was one of the relatively rare breech-lock mounts and towards the end, FD lenses were redesigned to lock onto the bodies with a bayonet action.

Canon’s own offering for the FL/FD mount can be said to be of high quality, but naturally not all can be said to have been optically ambitious designs. With the popularity of Canon’s FD mount cameras, the mount attracted a number of third party lens makers, with typically colourful results regarding optical quality.

The Contax/Yashica (a.k.a C/Y) mount was a mount designed by engineers at Zeiss (Oberkochen) for use by the line of Contax and Yashica SLR’s. Somewhat incongruously, both Contax and Yashica -branded cameras were designed and manufactured by Yashica, with one line (Contax) intended to be the the high-profile offering, whereas the other (Yashica) was to have broader appeal.

What makes the C/Y mount especially interesting, is the wide lineup of Zeiss-designed lenses available for the mount (and some of the available Yashica -branded lenses should also not be sneered at).

The Konica AR mount followed on the footsteps of the short-lived Konica F mount. While Konica designed a wide range of lenses (many of exceptionally high optical and build quality), for the Konica AR mount, few third-party manufacturers tried to enter the market.

In contrast to other significant Japanese Camera makers, Konica never made the transition to autofocus. Due to the exceptionally short FFD (for an SLR) of the Konica AR mount, Konica AR lenses could not be adapted (without optics) until the advent of mILC’s. In effect, Konica lenses languished for decades without any significant interest, and have only recently again found a clientele.

Some of the older, yet easily adaptable lenses can be found in LTM (Leica thread mount). LTM lenses are seen as especially attractive in some circles because they combine the small size inherent to rangefinder lenses with classic optical designs.

Due to its widespread use in mechanical rangefinders, and the often exceptional qualities of the optics, LTM lenses are in something of a renaissance. Even so, the short FFD of these lenses combined with the properties of digital sensors, can lead to surprising results (see more here).

Note also, that the LTM mount is a simple 39 mm thread mount and as such is physically identical with the M39 thread mount used by (among others) photographic enlarger lenses as well as the Zenit M39 SLR lenses. Hence, some risk of confusion exists.

The M42 lens mount is probably the most wide spread lens mount ever, used by dozens of camera and lens manufacturers. It is rugged and exceedingly simple. That said, towards the later stages several variations were introduced (see linked article for details). For purposes of adapting, M42 lenses can be used on all mILC’s and most SLR’s, albeit with some SLR’s (those with a longer FFD) not without an adapter with optics.

A veritable plethora of companies manufactured lenses for the M42 mount, and while some of these companies were keen on designing high-quality optics, others were more intent on making a low-cost (and typicaly, lower quality) offering.

Minolta SR (a.k.a. Minolta MC/ Minolta MD) was Minolta’s proprietary lens mount for the pre-autofocus age, later superseded by the Minolta (Sony) A mount.

As with most popular mounts of this era, third-party manufacturers have contributed strongly. Even so, Minolta’s own offering are generally considered to be of high optical and mechanical quality.

Olympus Four Thirds is by some margin the newest mount on this list. Having been launched in 2003 to be used with (initially) Olympus’ digital SLR’s, the lens mount was discontinued only ten years later in favour of the micro Four thirds mount (for mILC’s).

Due to the comparably small image circle of Four Thirds lenses (designed for a crop factor of 2.08), Four Thirds lenses are of limited use to cameras with larger sensors. Nevertheless, these lenses form an interesting alternative for users of MFT cameras.

In contrast, Olympus OM lenses are a widely attractive option for users of a broad range of digital camera users. Due it’s exceptionally long FFD, OM lenses can be adapted not only to mirrorless cameras, but also to several families of dSLR’s.

Alike Minolta SR and Canon FD, the Olympus OM mount was quite popular, and attracted wide attention from third party lens makers. Olympus’ lens offering for the OM system is generally considered to be of very high optical and mechanical quality while often also being among the smallest and lightest alternatives.

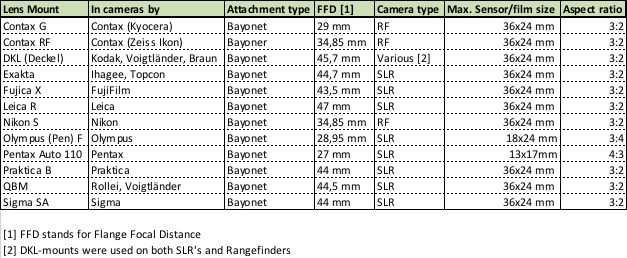

Interesting (but relatively rare) legacy lens mounts

Again, some words of explanation and elaboration are in order.

The Contax G mount, used by the Contax/Kyocera series of rangefinder film cameras (manufactured 1994-2005) makes it onto the list partially because the relatively small range of lenses designed for the Contax G mount were all of exceptionally high quality, and partially because mirrorless digital cameras have given these lenses a new lease on life.

Not to be confused with the former, the Contax rangefinder mount was designed to be used with early Zeiss Ikon (“Contax”) rangefinder cameras (from 1932 onward). The same mount was later adopted also by some other (mostly Soviet) rangefinder cameras, and is therefore also known as the Contax/Kiev -mount. As with most lens mounts, the repertoire of lenses is colourful, but especially the original Zeiss designs for the Contax rangefinder are held in very high regard.

If you’ve never heard of DKL (or ‘Deckel’) mount lenses, don’t be surprised. DKL lenses were used on a range of early SLR’s and rangefinders, and the mount would otherwise easily have slipped into oblivion, except that many lenses for DKL-mount cameras were made by rather highly respected manufacturers (e.g. Rodenstock, Schneider-Kreuznach, Voigtländer). Due to the construction of the DKL mount, these lenses are sadly often unable to reach extremely high (low number) f-stops, but that can be compensated by the otherwise quite striking characteristics of (some of) these lenses.

The Exakta (sometimes spelled Exacta, often abbreviated EXA) mount were used by the eponymous range of cameras manufactured by Ihagee, and also adopted as one of the lens mounts used by famed Japanese camera manufacturer Topcon. While not all the lenses are exceptional, singularly high-quality lenses for the Exakta mount were manufactured both by Topcon as well as other well-known German players (Carl Zeiss Jena, Meyer-Optik, Schneider) and others.

The Fujica X mount was Fujifilm’s proprietary mount after also Fujifilm stopped making their cameras in M42-guise. N.B! Do not confuse this Fujica X-mount (1970’s–80’s) with the current Fujifilm X-mount for digital mirrorless cameras. While significantly less successful than some other Japanese proprietary mounts and short-lived, the Fujica-X mount nevertheless sports some very interesting lenses.

Leica, while best known for its rangefinder cameras, also made film SLR’s for SLR-type cameras for almost half a century, using the Leica R bayonet mount. Leica R lenses are not a budget option, and also not in excessive supply, but are nevertheless highly interesting due to a combination of generally very high optical quality, and a Flange Focal Distance, that not only allows smooth adaptation on mirrorless cameras, but also many SLR-cameras (digital and film). Note! As typical for many long-lived lens mounts, the mount progressed somewhat during its lifetime, leading to that within-system compatibility is not universal.

Alike many Japanese camera companies, also Nikon started by making rangefinder cameras. Holding with the spirit of the era, Nikon’s rangefinder mount (generally referred to as Nikon S) was a copy of the Contax RF mount, but with some subtle differences which led to incompatibilities with some lenses. Just as with the Contax RF mount, the Nikon S mount is interesting due to the existence of some exceptionally fine lenses.

Back when Film was not only something you indulged in, Olympus introduced a series of half-frame SLR’s, under the name Olympus PEN. By shooting half-frame (in portrait orientation), the Pen was able to cram double the number of pictures on a roll of film. With the PEN, Olympus introduced a new mount (the Olympus PEN F-mount) and a range of lenses, which are interesting due to combination of high-quality optics and a comparably diminutive size. If you’re interested in adapting these lenses, you should be aware of that all of these lenses do not cover the full-frame sensor, but should be quite usable on APS-C type cameras.

Also Pentax wanted to introduce an interchangeable lens camera smaller than ordinary SLR’s, and Pentax’s solution was the adoption of the smaller 110-type cartridge film in the design of the Pentax 110-series of mini SLR’s. While the repertoire of Pentax 110 lenses is relatively diminutive, the lenses themselves are (while also diminutive) of high optical standard, and have been successfully adapted to be used on crop-factor mILC’s (especially Micro Four Thirds).

In the end, also Pentacon (of East Germany, makers of the popular Praktica SLR’s) abandoned the M42 mount, and introduced the Praktica B-bayonet mount. Lenses for the Praktica B-mount were mostly supplied by Pentacon and Carl Zeiss Jena, making Praktica B-mount lenses relatively interesting.

QBM stands for “quick bayonet mount” and was the bayonet mount adopted by Rollei for their line of Rollei / Voigtländer 35 mm SLR’s (1970’s through 1980’s). The QBM mount is interesting because many lenses for the system were of generally high quality (as indicated by that many of the Zeiss lenses made for QBM were recycled in the more well-known guise of the Contax/Yashica mount).

Sigma is (and has for a long time been) one of the foremost third-party lens manufacturers, and many have used Sigma lenses with mounts by the major players (Canon EF, Nikon F, Pentax K, Sony A, etc. ). What some have missed, is that Sigma also has had its own line of cameras, using the Sigma SA mount. While certainly less widely available as Sigma’s lenses for other mounts, Sigma SA lenses are available in the marketplace, and might offer one route to adapting Sigma lenses.

Footnotes:

[1] There’s a reason I omitted Sony from the major camera makers (having an uneasy relationship with third party lens makers), namely that Sony makes interface specifications for its E and FE mounts available to third parties without a fee (https://www.sony.net/SonyInfo/News/Press/201102/11-018E/).