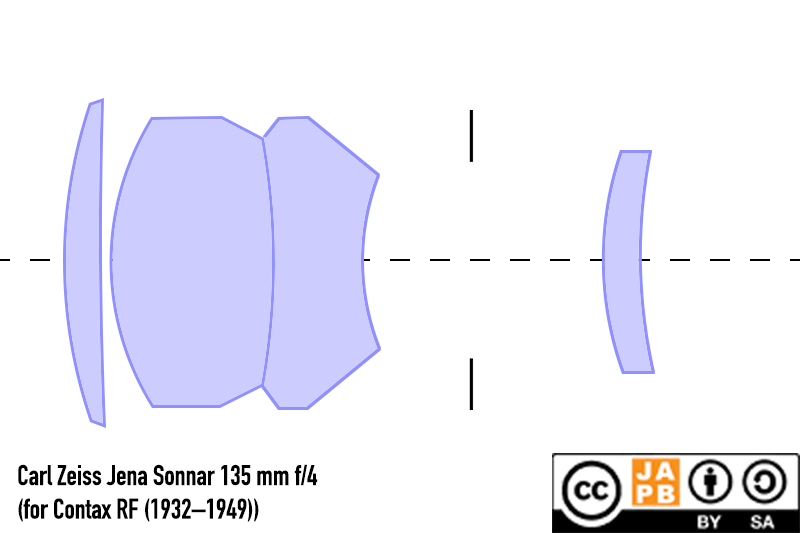

This article tries to detail the development of an arguably very influential lens design: that of the 1932 Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 135 mm f/4 – a design of the Sonnar family of lenses originally developed for the 1932 Contax rangefinder.

The Sonnar family

The Sonnar lens design is among the most illustrious photographic lens designs ever. Ludwig Bertele’s fundamental innovation was to design lenses that use a high element-to-group ratio (e.g. a 7 element, 3 group lens) in order to lessen flaring and improve transmittance, hence for the first time enabling the development of super-bright lenses.

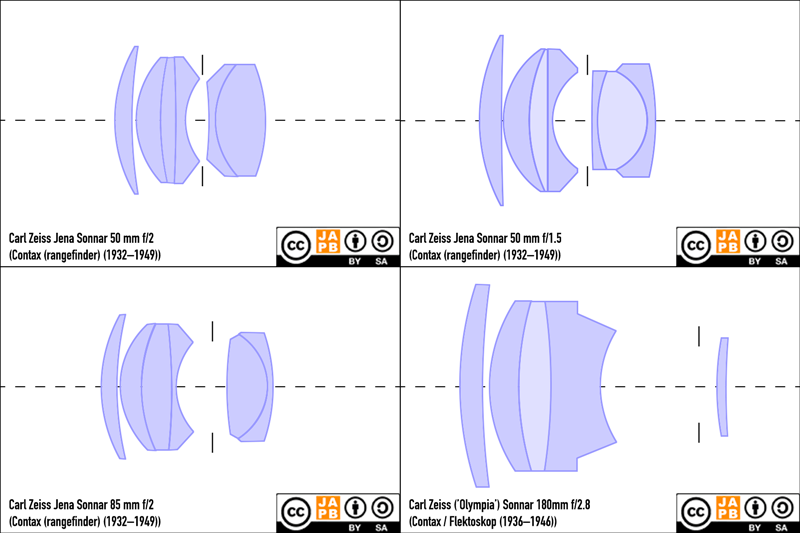

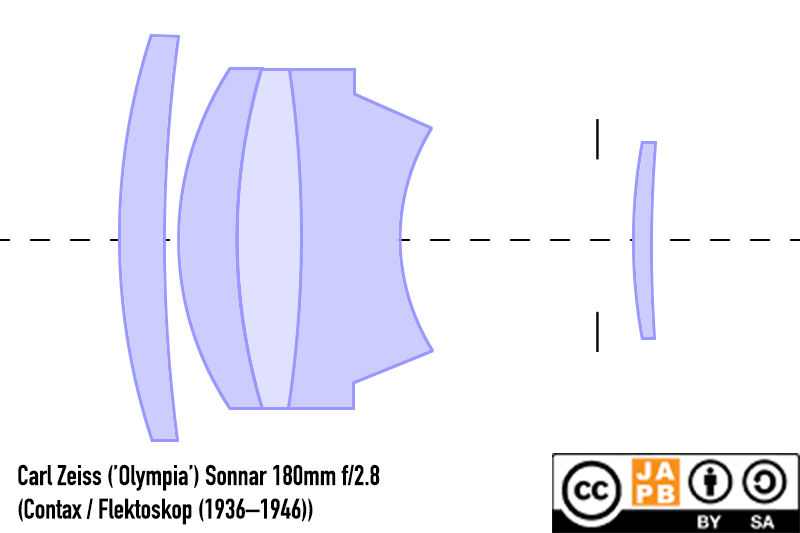

Starting with a relatively affordable 50 mm f/2 lens (for the late 1920s f/2 was faaast), the family of Sonnars was quickly (1932) extended with an even faster 50 mm f/1.5 lens [data sheet], a fast portrait lens in the 85 mm f/2 (also 1932) and a fast tele lens with the 1936 Olympia Sonnar (180/2.8) and a for its time crazy fast 300 mm f/4.

And a (1932) 135 mm medium tele that – with a maximum aperture of at f/4 – (compared to the other Sonnars) was decidedly not fast. I’d understand if you thought that in this family of crazy fast lenses the 135 mm f/4 is a bit of the odd one out. I even share that thought.

Even so, one could argue that the 135 mm Sonnar outlasted them all. Introduced in 1932 it was manufactured almost uninterruptedly and with very minor changes all the way until the Berlin wall came down.

In many ways Bertele’s 135 mm Sonnar from 1932 epitomises the entire development of the mainstream photographic industry – from the 1930s to the advent of the autofocus era. This also makes it a case study for a considerable portion of entire 35 mm camera industry. While this genealogy will mention some lenses that diverge somewhat from the original concept of the Sonnar (a high elements-to-groups ratio), I have focused it on only Carl Zeiss Jena and Carl Zeiss and only on those designs that show a clear link to the original 1932 concept.

Methods…

Note please: While there are several sources that I regularly deem trustworthy, they tend to focus on a specific lens design, and often do not elucidate the development of that specific lens. Therefore, this article is based mostly on the detailed study of close to 1000 samples of various generations of the 135 mm Sonnar found online, most of which1 luckily display their serial number proudly2. In combination with that Carl Zeiss Jena (pre-war and East German) and Carl Zeiss (West German and post-unification) both have been conducting a running numbering scheme, these images allow tracing the development quite systematically3.

However, there are sources that I am aware of that I do not have access to4, the lack of which might conceivably lead to somewhat less precision (and even the occasional error). Once I have access to these, I will obviously extend this article as needed.

I will also extend information on serial numbers with estimates on production years, using the oft-cited table of Zeiss serial numbers and fabrication years, even though this table is clearly lacking in precision.

Generation 1: Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 135 mm f/4 for the Contax rangefinder (1932–1949) [data sheet]

The entire Sonnar family was originally developed for the Contax rangefinder by Zeiss Ikon (camera manufacturing arm of Carl Zeiss Jena). It is therefore by no means surprising that this is also where the 135 mm f/4 Sonnar saw its use during the 30s and 40s.

This first generation differs from subsequent generations in that there are not so much distinct versions of the lens. Instead there is a design evolution with new features replacing old features in stages. Sometimes two changes would occur at once, whereas at other times these would seem to follow each others in a more haphazard manner (typically an indication of parts stores being exhausted before starting to use the new parts).

Optical design

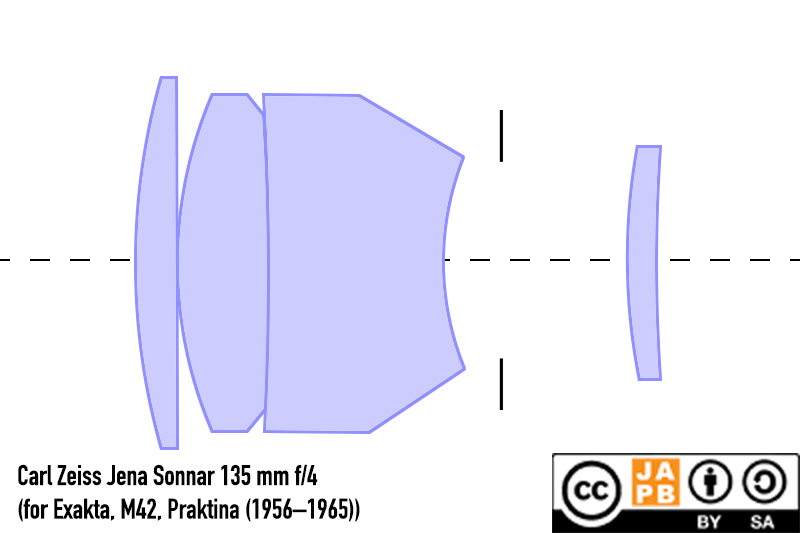

While not sharing the 50/1.5 Sonnar’s extreme elements-to-groups ration (7 to 3), or – more generally the use of triplets at the front-end, the 135/4 Sonnar is still recognisably a Sonnar.

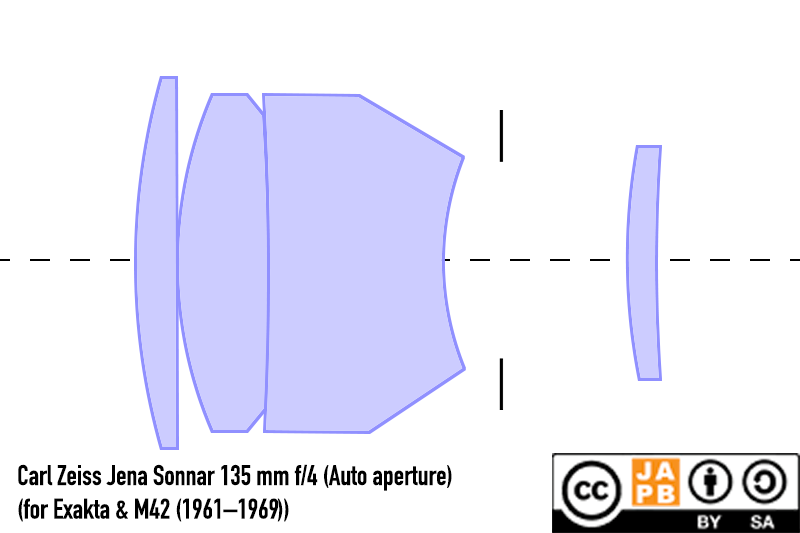

The 135/4 sports a 4 elements in 3 groups design, characterised by a single lens, a narrow air gap, a doublet made out of (comparatively) huge chunks of glass, a large air fap followed by a single positive meniscus. This design would – as you will see – in the coming decades become iconic.

The within-generation evolution of the 135 mm Sonnar

• In terms of outward appearance, there are three barrel designs: silver (polished metal); black-and-chrome; all-chrome. At a distance it is not always easy to distinguish a silver and chrome version.

In terms of design evolution the progression is from polished metal to black-and-chrome (≈1933); from black-and-chrome to all-chrome (≈1936) and from all-chrome to polished metal again (≈1945)5.

• Early samples have big numbers on the focusing ring, which are later (≈1936) exchanged against considerably smaller lettering.

• The ribbing of the control rings (focus and aperture) is very tight in early and wartime samples and changes to clearly less tight (Sparse) design around the end of the war.

• Post-war lenses lack the lowest ribbing.

• Starting from 1945 these lenses systematically have the red letter T indicating that they are coated. At the same time that red letter T does make its appearance on some samples from as early as 1941.

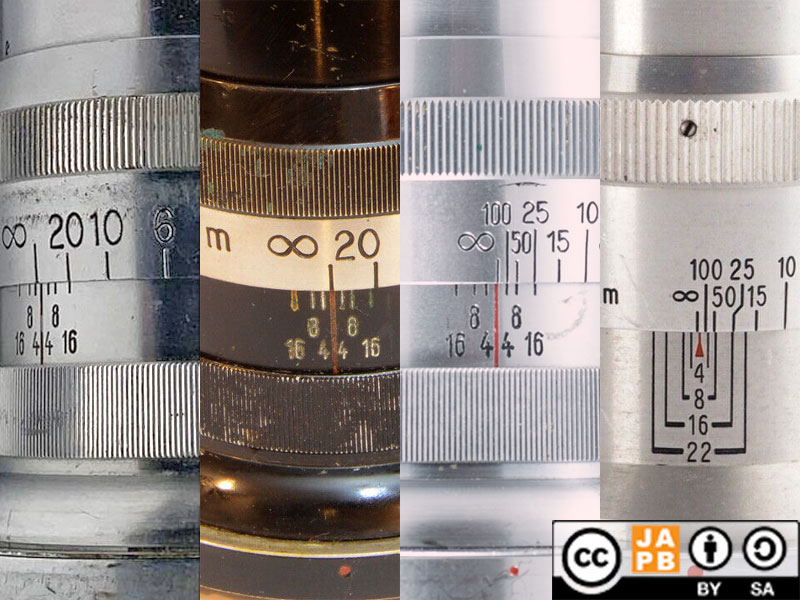

I obviously do not have samples of each type on hand, but I’ve managed to see several at various vintage lens meets and have managed to take pictures of several. The collage below traces the main developments of the CZJ (Contax) 135/4 Sonnar:

• 1932 sample, chromed brass, big numbers, tight ribbing

• 1934 sample, black-lacquered and nickel-plated brass, big numbers, tight ribbing

• 1937/8 sample, chromed brass, small numbers, tight ribbing

• 1949 sample, brushed metal, small numbers, no ribbing at base, improved DOF scale

I have not given serial numbers above, and the dates above are approximates, because there are several instances where a serial number range contains samples of both an earlier and a later design, without the later design necessarily being the later serial numbers.

In 1949 Zeiss Ikon (East) unveiled the Contax S – their next generation camera. Importantly, the Contax S was an SLR camera that no longer used the Contax rangefinder’s mount (the Contax/Kiev mount), instead using the M42 mount. Carl Zeiss Jena needed all its resources (that had been depleted by war, bombings and reparations) to focus on the new up-and-coming family of cameras. Manufacturing lenses for the aged Contax family of rangefinders was therefore unceremoniously dropped.

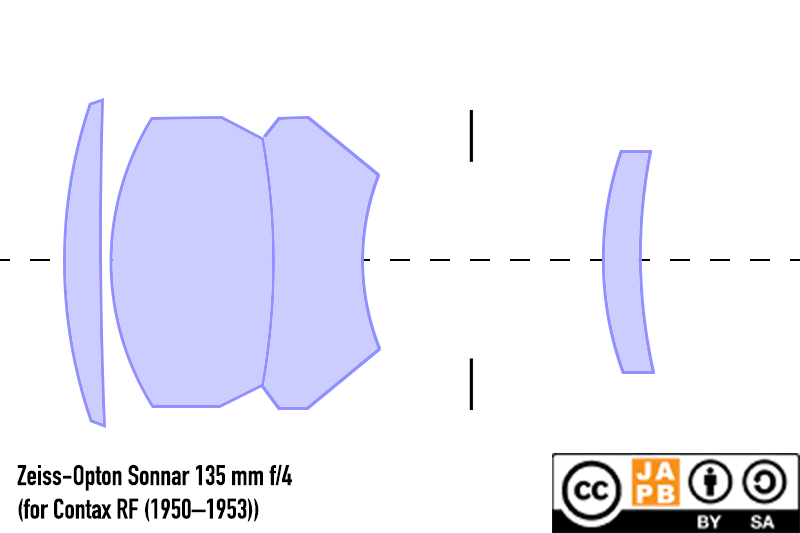

Generation 1 redux: Zeiss-Opton Sonnar 135 mm f/4 for the Contax rangefinder (1950–1953)

When Zeiss Ikon (East) unceremoniously dumped the Contax rangefinder, Zeiss Ikon (West) stepped in. Whether this was just the right move for cameramaker Zeiss Ikon (West) and lensmaker Zeiss-Opton (West) who needed a hit product to get their production up to speed and get started on their way towards economies of scale or whether this was the West German arm of Carl Zeiss placing their bets behind the curve (if so, this would be the first such decision of many to come) is still being debated.

Whatever the rationale, Zeiss-Opton essentially continued producing the 135 mm f/4 Contax Sonnar6 exactly where Carl Zeiss Jena had left it. Outwardly, the only two things that distinguish a Zeiss-Opton version from a postwar Carl Zeiss Jena version is on the lens’ name ring: “Zeiss-Opton” instead of “Carl Zeiss Jena” and “135 mm” instead of “13,5 cm”.

I’ve not been able to identify more than a dozen samples of the Zeiss-Opton 135 mm Sonnar (SN range: 92160–1130813), but these serial numbers would indicate that the manufacture of the 135 mm Sonnar ended in Oberkochen in 1953 7. This is also the same year that Zeiss Ikon (West) introduced its first Contaflex series SLR.

Generation 2 (East): Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 135 mm f/4 (Preset) for SLRs (≈1956–1965)

After having spent the end of the 40s and the early 50s very fruitfully (developing such legendary lenses as the 75 mm Biotar, and after having independently perfected8 the retrofocus design), the mid 50s saw Carl Zeiss Jena re-evaluating some of its earlier rangefinder lenses, specifically looking at redesigning these for use in the increasingly significant SLR market. In this it was clear that the 135 mm f/4 Sonnar would initially complement and subsequently replace the Carl Zeiss Jena 135 mm f/4 Triotar [data sheet].

From 1956 the 135/4 Sonnar was available for the Exakta, M42 and Praktina mounts as preset lenses. 1961 sees the introduction of the 135/4 Sonnar also as an auto aperture variant (see next) and thereafter the manufacture of these preset lenses abates rapidly with the last preset lenses being manufactured ≈1965. The Serial number range is 4876115–7236148.

In terms of the outward design of the Generation 3 lenses, there seems to be no variation: All lenses feature an all-silver (brushed aluminium) barrel and dual aperture rings (aperture ring and preset ring).

Generation 2 (West): Carl Zeiss Sonnar 135 mm f/4 (Contarex) (1958–1972) [data sheet]

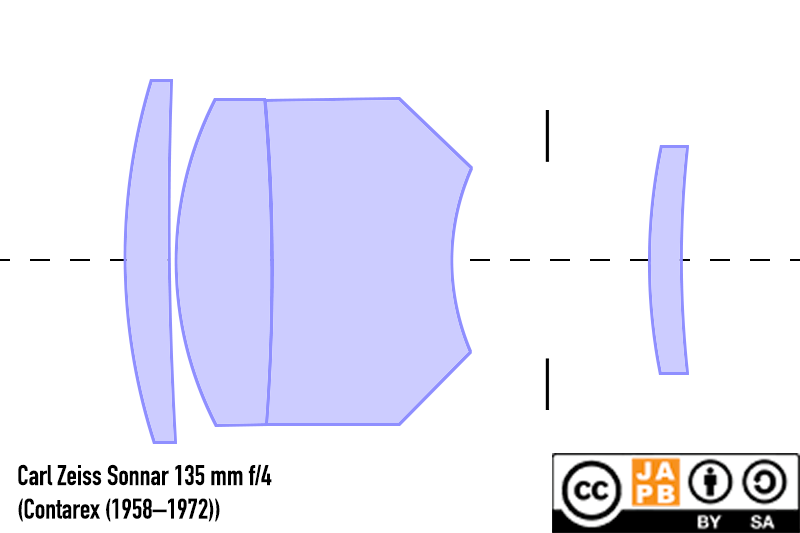

Zeiss Ikon (West) Introduced its tour de force camera the Contarex in 1958 together with an initial lineup of lenses. This initial lineup included many classic Carl Zeiss/Carl Zeiss Jena designs, including a 135 mm f/4 Sonnar.

Initially (1958–≈1963) the outward design of Contarex lenses used an all-over matte, silver-coloured finish (sometimes referred to as ‘chrome’ (Serial numbers until 3595961). After 1963 all Contarex lenses were painted a glossy black, with only the (narrow, ribbed) focus ring remaining silver in colour.

While outwardly the Contarex Sonnar looks very different from the Zeiss-Opton Sonnar 135 mm f/4 for Contax (above), the optical design is remarkably consistent and the common ancestry with the 1932 Sonnar 135 mm is beyond doubt.

Side note: Other 135 mm Sonnars from Carl Zeiss (West)

The f/4 Contarex 135 mm Sonnar however was to be the last lens manufactured by Carl Zeiss (West) that can be clearly derived from the original 1932 Sonnar for the Contax rangefinder.

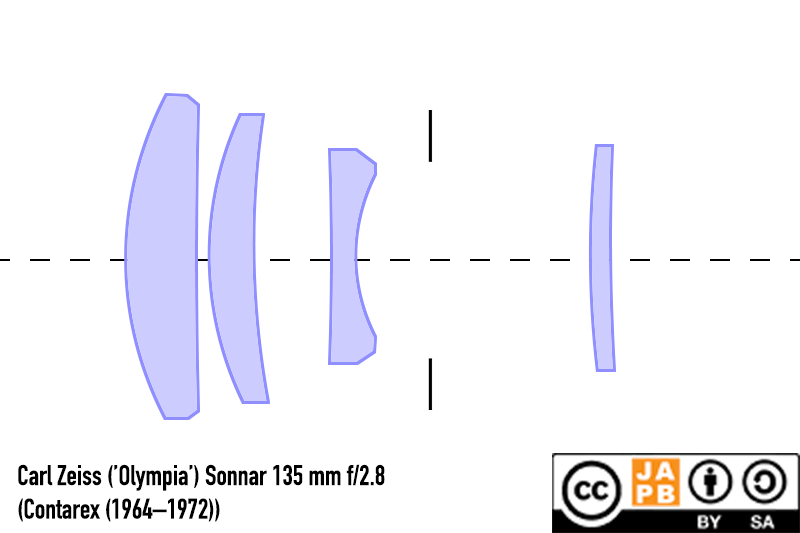

While Carl Zeiss would in the coming years market a long list of 135 mm lenses under the name Sonnar, these are not so much related to the 1932 4 elements in 3 groups design, but are more modernisations of the 1936 180 mm Olympia Sonnar with its 5 elements in 3 groups design (below).

For example (and I do not pretend this listing to be exhaustive):

• The 1964 Carl Zeiss Contarex 135 mm f/2.8 uses a 4 elements in 4 groups design where the central element of the 1936 Olympia Sonnar’s triplet has been replaced by an air lens9.

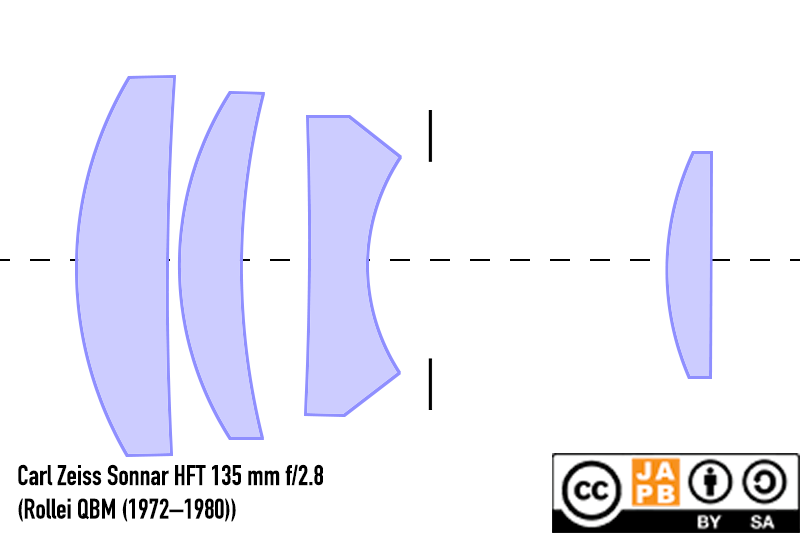

• The 1972 Carl Zeiss Sonnar HFT 135mm F/2.8 (for Rollei QBM) uses a design very similar to the design of the Contarex 135 mm f/2.8 (above) with the one difference that the rear positive meniscus has been transformed into a plano-convex element.

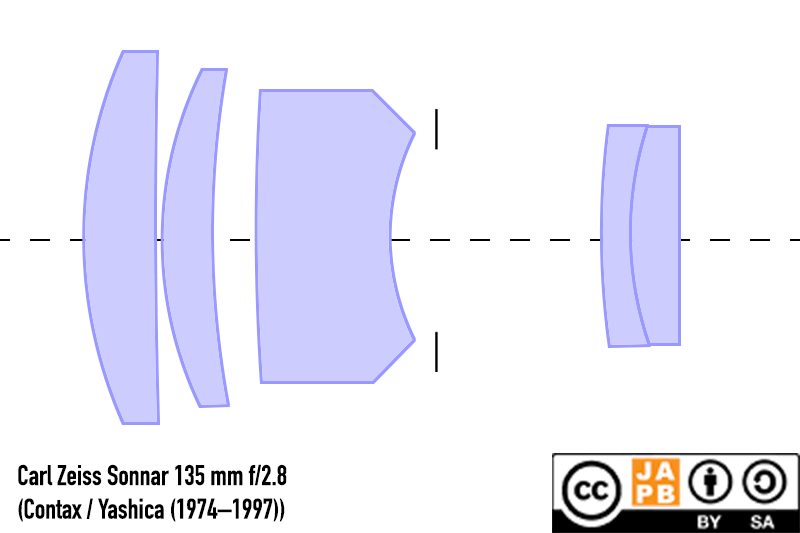

• The 1974 Carl Zeiss Sonnar T* 135mm F/2.8 (for the Contax/Yashica mount) takes the design used in the Contarex and Rollei QBM (above) and keeps the front group largely as it is, but replaces the rear plano-convex rear lens with a doublet resulting in a 5 elements in 4 groups design.

Hence, while the 1958 Sonnar 135 mm f/4 for the Contarex would end up being the last 135 mm Sonnar manufactured by Carl Zeiss (West), the original design would be carried forward on the other side of the iron curtain.

Generation 3 (East): Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 135 mm f/4 (Auto Aperture) (1961–1969)

While all Carl Zeiss Jena preset lenses had been of a uniform design, in this generation there is comparatively immense variation. When the first auto aperture models (Exakta and M42) make their appearance in 1961, they also introduce a black-painted barrel with a narrow faux-leather (rubber) focus ring. In-between CZJ experiments with a rubber ring that carries large, prominent diamond shapes, but that experiment does not hold10.

In ≈1964 the manufacture of the Zebra design begins, and while some lenses still leave the factory with earlier designs, it is clear that this is just CZJ making sure to use up parts stocks.

In ≈1966 CZJ introduces the new, faster 135 Sonnar (see next), but that new version is only being offered in M42 mount. Exakta lenses continue to be (albeit in dwindling numbers) produced according to the slower scheme. The last 135/4 Sonnar in Zebra guise leaves the factory around 1969 (#8437017)

Interestingly it seems that the optical design has remained entirely unchanged between the Preset and Auto aperture versions.

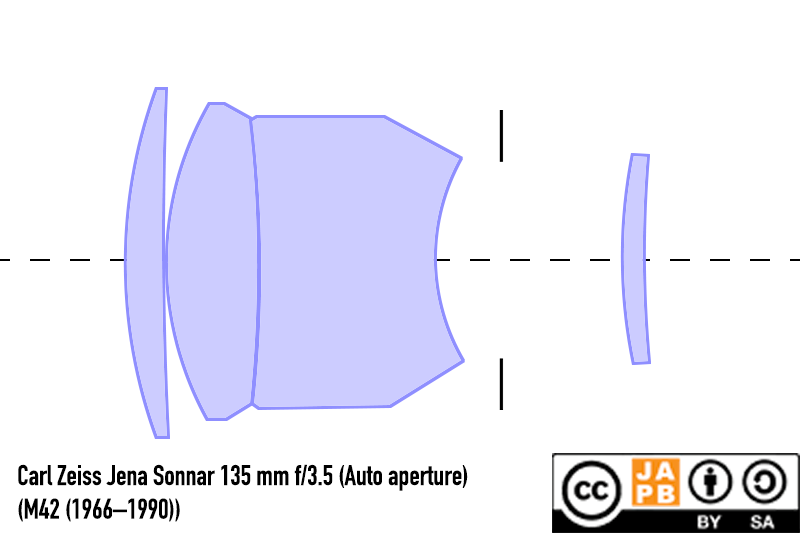

Generation 5: Carl Zeiss Jena Sonnar 135 mm f/3.5 (Auto Aperture) (≈1966–1990) [data sheet]

In 1966 (Earliest SN: 8135333) CZJ starts manufacturing a new, slightly faster version of the auto aperture M42 lens. Importantly, this faster version is never manufactured for the Exakta mount which at this stage is clearly showing its age (and falling market traction). Initially the new, faster 135 mm Sonnar uses the same Zebra design and is outwardly barely distinguishable from the earlier, slower Sonnar.

The new (slightly modified) optical scheme adopted in the f/3.5 version seems to remain unchanged from 1966 to 1990. The cosmetic/ergonomic design is however updated in 1975 (earliest SN: 9900251) when CZJ changes to an all-black design sporting a broader focus ring patterned with small pyramids. In terms of ergonomics there is also a change as CZJ moved from and auto-only aperture mechanism (with manual stop-down lever) to a more industry standard A/M-switch design,

The aperture mechanics were redesigned in 1976/77 leading to two sub-types. Both sub-types were multicoated, and cosmetically both sub-types were of the all-black design. For imagery comparing the late version’s first and second subtypes, I have to refer you otherwhere.

The later design remains all the way till the last samples manufactured for the M42 mount (latest SN: 166336, after SN reset).

Interestingly, while in zebra guise the 135 mm f/3.5 Sonnar was never manufactured for the electric variant of the M42 mount. Instead, the M42 electric makes its first appearance (earliest SN: 10003630, ca. 1975) after the introduction of the new design. The manufacture of the electric version of the 135 Sonnar was also discontinued (latest SN: 7236, after reset) well before the manufacture of the auto aperture M42 lens ended.

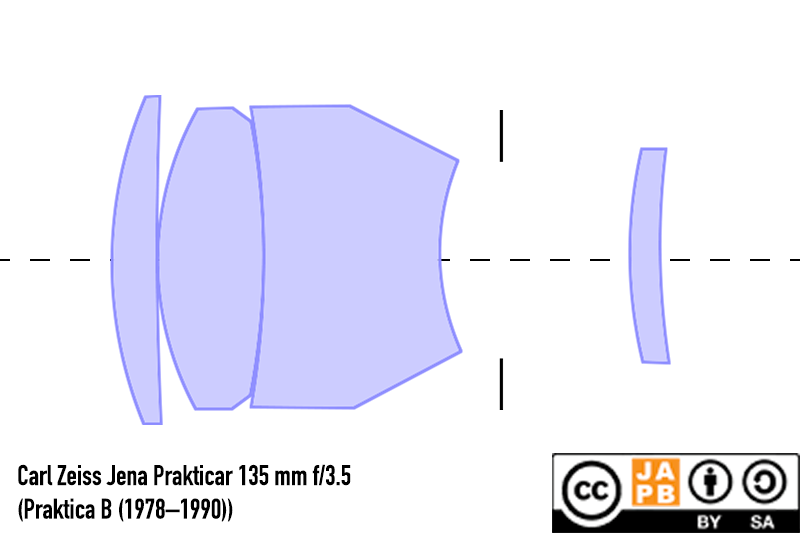

Generation 6: Carl Zeiss Jena Prakticar (Sonnar) 135 mm f/3.5 (1978–≈1990) [data sheet]

Pentacon launched the Praktica B mount together with a new series of camera bodies in 1978. In tandem CZJ launched versions of many of its trusty M42 lenses (including the 20 and 35 mm Flektogons, 50 and 80 mm Pancolars and 135, 180 and 300 mm Sonnars).

Optically there was practically no change to the contemporary 135 mm f/3.5 Sonnar in M42 mount, but outwardly the early Prakticar lenses – whether manufactured by CZJ or by Pentacon – all followed the same design and style.

Unlike all previous iterations (above) of the 135 mm Sonnar, this lens (as with all Prakticar lenses) omits mentioning the optical design ‘Sonnar’. Another (for the purpose of this article) key difference is that the serial number of the lens is no longer prominently visible. Instead, it’s only faintly engraved in the black plastic at the bottom end of the mount. This has made it difficult for me to trace the version numbers of samples online as sales images rarely focus on this aspect of the lens.

And then the wall came down…

It would be somewhat disingenuous for me to put forward that the original 1932 design would still be manufactured had not the wall come down, plunging the East German optics industry into chaos and forced integration into West German businesses.

While all the 135 mm Sonnars that are derived from the original 1932 design are able to take very good pictures (offering a good balance of sharpness, colour, bokeh, etc.), it must be said that by the 1980s, that original 1932 design had become relatively outdated. It is worthwhile to remember that Bertele’s original 1920s innovation in designing lenses that extensively used doublets and triplets was predicated on the imperative to keep the number of glass-air interfaces as low as possible (as lens coatings did not yet exist). Therefore Bertele designed a range of lenses (from the 50/1.5 Sonnar to the 180/2.8 Sonnar) that employed triplets (three elements cemented together), where the central lens was intended to emulate an air lens as closely as possible.

By the mid 1960s, coating technology had advanced to the point where lenses could realistically be designed to use real air lenses (instead of complicated triplets). This not only saved on cost and weight, it also circumvented what always has been the bane of any lens design that relies on cemented lens elements: element separation. In this sense Carl Zeiss’ (West) 1964 departure from the original (4 elements in 3 groups) 135 mm Sonnar design must be seen as the correct move. Not only did it allow more economical, more reliable lenses, it also opened the door to increasing the maximum aperture of the 135 mm Sonnar beyond what the original design could stretch to.

While today undoubtedly outdated, the 135 mm Sonnar’s 1932 design was a prominent fixture of still photography for more than half a century. During that time, it witnessed:

– the rise of SLRs to replace rangefinders as the tool of choice of enthusiast and professional photographers

– the evolution from manual aperture to preset aperture to aperture automation.

– the gradual replacing of precision mechanics metals such as brass with cheaper and lighter metals, to later be complemented with rubber and even replaced by plastics.

– the advent, proliferation, evolution and finally ubiquity of lens coatings

Not bad for a design that (in terms of specifications) was clearly the ugly duckling of Bertele’s Sonnar family.

Footnotes

- As a pesky exception to the rule, The Praktica B mount lenses did not display their name on either the name ring or the lens barrel, but only on the rear-end of the mount, and only as an engraving (without ink). Hence, I have often failed in deciphering the numbers of Praktica B mount 135 Sonnars and they are therefore underrepresented here. ↩︎

- Online samples have not been included unless their serial number can unequivocally be deciphered. ↩︎

- Any serial numbers or serial number ranges mentioned here are based on samples found. Therefore when I identify a specific version and give the serial number range that I have identified (e.g. “Earliest SN: 111111; Latest SN: 222222” or simply “111111–222222” ) that does indicate that the version was produced as early as SN 111111 and as late as SN 222222, but it does not indicate that there could not be even earlier or even later samples. ↩︎

- This applies specifically to H.Thiele’s Fabrikationsbuch Photooptik II = Carl Zeiss Jena 1927 bis 1991 ↩︎

- Importantly, there seems also to be a change in material around 1945 because earlier are reported to generally be considerably heavier. The postwar era generally saw a turn away from steel and towards aluminium, so I deem it likely to have happened here as well. This would also mean that while the earliest and latest Carl Zeiss Jena Contax Sonnars share a polished meta appearance, the metal itself would have changed. ↩︎

- As well as most of the range of Carl Zeiss Jena’s Contax lens lineup… ↩︎

- Manufacture of the West German versions of the Contax continued to 1961. ↩︎

- It seems Angenieux in France and Carl Zeiss Jena in East Germany were able to almost simultaneously and independently develop the retrofocus design used ever since by 99% of all wide-ange SLR lenses. ↩︎

- This might feel like an odd move, but one needs to consider that Bertele’s original Sonnars often used triplets where the central lens element was made of such sorts of glass that it would act almost as an air lens, but without the loss in transmittance and increase in flaring that a real air lens unavoidably meant in the era before effective lens coatings. ↩︎

- While many sources indicate that CZJ moved from the faux-leather band to the rubber diamond band (before then moving then to the ‘zebra’ design), existing samples and their serial numbers indicate that the rubber diamond design (earliest observed serial number: 6539956; last observed serial number: 6928361) was partially simultaneous with the faux leather design (6307376–7198302). ↩︎

Comments